Last week I published a talk that I had given at the Palais de Beaux-Arts in Brussels. The talk, ‘The many roots of Christian Europe, the many sources of to Islamic world’ was one in a series given to accompany an exhibition, ‘The Sultan’s World: The Ottoman Orient in Renaissance Art’, organized by Bozar, the Centre for Fine Arts.

It is a groundbreaking exhibition that focuses on the period from the late fifteenth century to the early seventeenth, the period in which the extent of Ottoman rule in Europe was at its greatest – the Ottoman Empire stretching to the ‘gates of Vienna’. The proximity of the threat posed by the Ottomans often led to fear and demonization. But this was also a period of great tumult in European self-understanding. In was in the Renaissance that Petrarch invented the term ‘the Dark Ages’ to describe the Europe of the Middle Ages, painting the millennium between the end of antiquity and the beginnings of the Renaissance as a time without culture or learning. It is to Petrarch, too, to whom we owe the term ‘Renaissance’, the ‘rebirth’ of culture and learning after the Dark Ages had expunged the flames lit by the great poets and philosophers and playwrights of Greece and Rome.

Few historians would use the term ‘Dark Ages’ today, recognizing it as a self-serving phrase employed by Renaissance thinkers to elevate the intellectual standing of their own era. But the phrase reveals something else too: the way that Renaissance thinkers saw Europe’s own immediate past as alien. The Other, in other words, lurked to a degree in Europe’s own history. This inevitably shaped the European perceptions of the Ottoman ‘Other’, particularly so because the Muslim world played a major role in reconnecting Western Europe to the Greek tradition, a connection that the division of Christendom into Western and Eastern Churches had helped sever almost millennium earlier. It was through the great Muslim philosopher Ibn Rushd’s translations, for instance, that most western European philosophers rediscovered their Aristotle, his commentaries shaping the thinking of a galaxy of thinkers from Thomas Aquinas to Moses Maimonides.

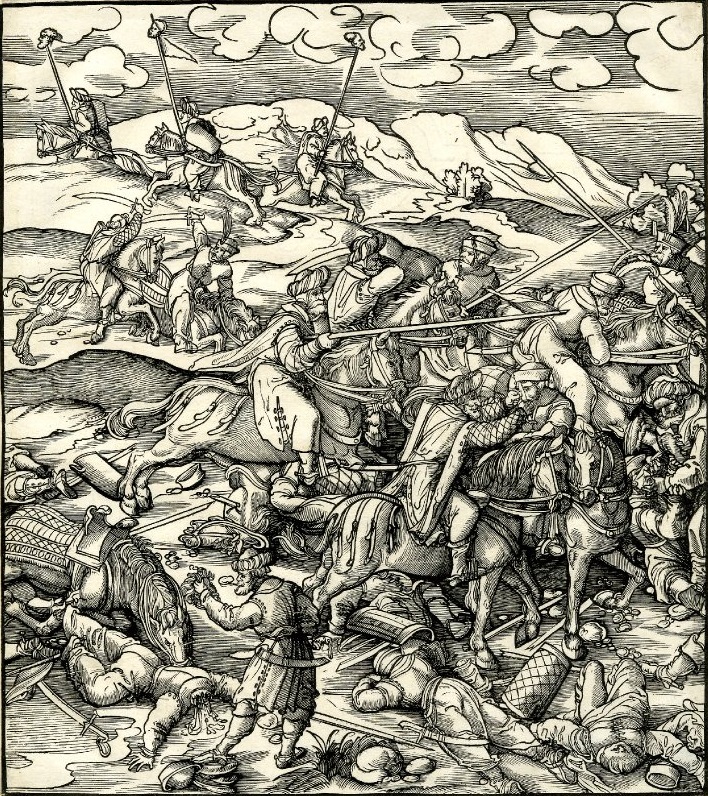

All this inevitably shaped Renaissance attitudes to the Ottoman Empire. There is little in the Bozar exhibition of the ‘harems, concubines, slave markets and steambaths’ kind of depiction that we see in, say, ninteenth century European art. There is certainly demonization – a whole section of the exhibition is given to ‘Visual Polemics’, the creation of a visual language through which to present the struggle between East and West, Islam and Christianity. The influence of the Reformation is striking here – many Protestant artists depicted Catholics as if they were Turks and the Pope as a kind of despotic Ottoman potentate.

What is striking about ‘The Sultan’s World’, however, is the far greater nuance that exists towards the Ottoman world. For intertwined with the fear is also curiosity, respect and even awe. There was a willingness, too, to view the Ottoman world not as demonic or exotic but as a variant of the European experience. As the Turkish novelist Elif Shafak writes in the catalogue, this is

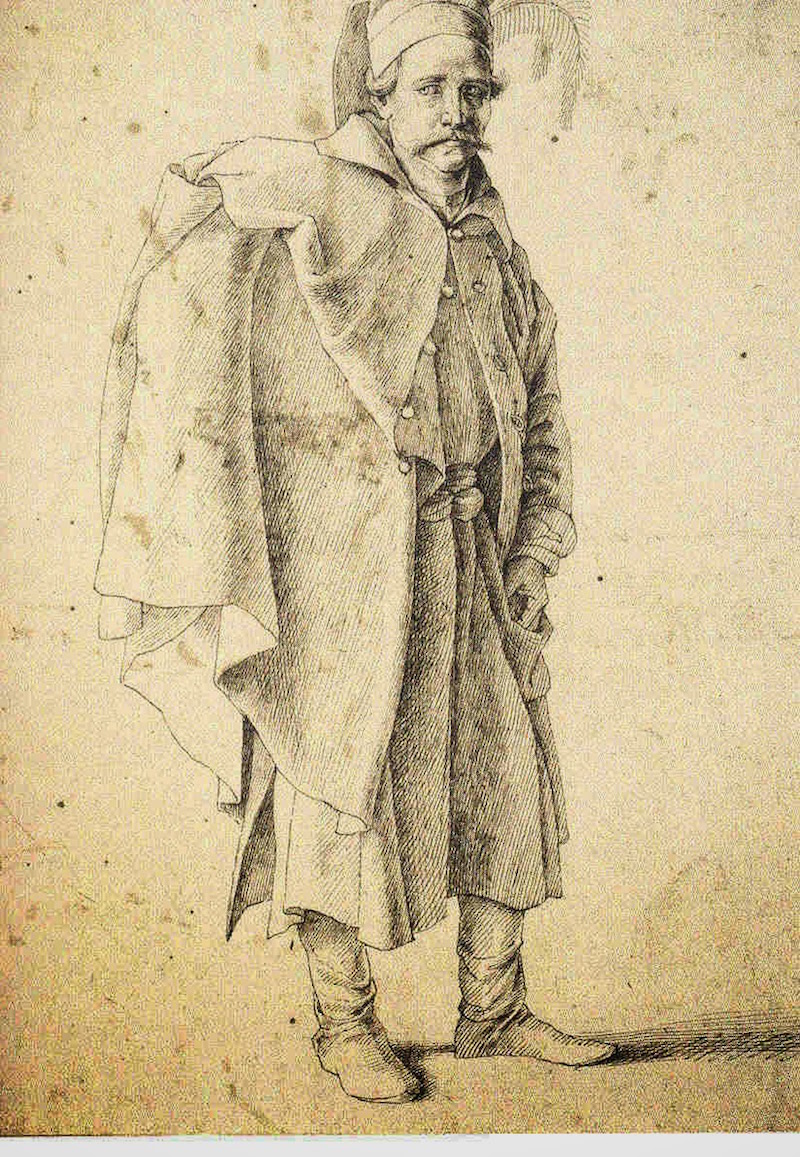

A multilayered exhibition that both challenges stereotypes and introduces fascinating nuances into the ongoing cultural debate. True, the Ottoman empire has long been ‘the Other’ in the eyes of Europe, and vice versa. But Ottomans and Europeans were not solely arch-enemies. Between the two, there has been a mesmerizing flux of ideas, commodities and individuals – merchants, pilgrims, travelers, diplomats, soldiers and captives of war… With the advent of the Renaissance the writings of humanists were important in introducing a more complex understanding.

Consider, for instance, Titian’s portrait of Roxelana, wife of Suleiman the Magnificent:

She is depicted in a beautiful velvet dress, her headdress adorned with peals and sapphires. She is portrayed as sexually alluring, but it is a very different kind of sensuousness than the Orientalist exoticism of later painters. Titian paints her in a way that he would any woman of power and authority. Compare the portrait of Roxelana with, for instance, Titian’s portrait of Eleanora Gonzaga, the Duchess of Urbino, that he had painted about a decade earlier:

There is here more of a sense of concealed sexuality. But Titian employs the same techniques – the attire, the jewels, the milky skin, the confident gaze, even the small animal, in one case marten, in the other a dog – to illustrates wealth, power, nobility, strong character, suggesting a common view across the east-west divide.

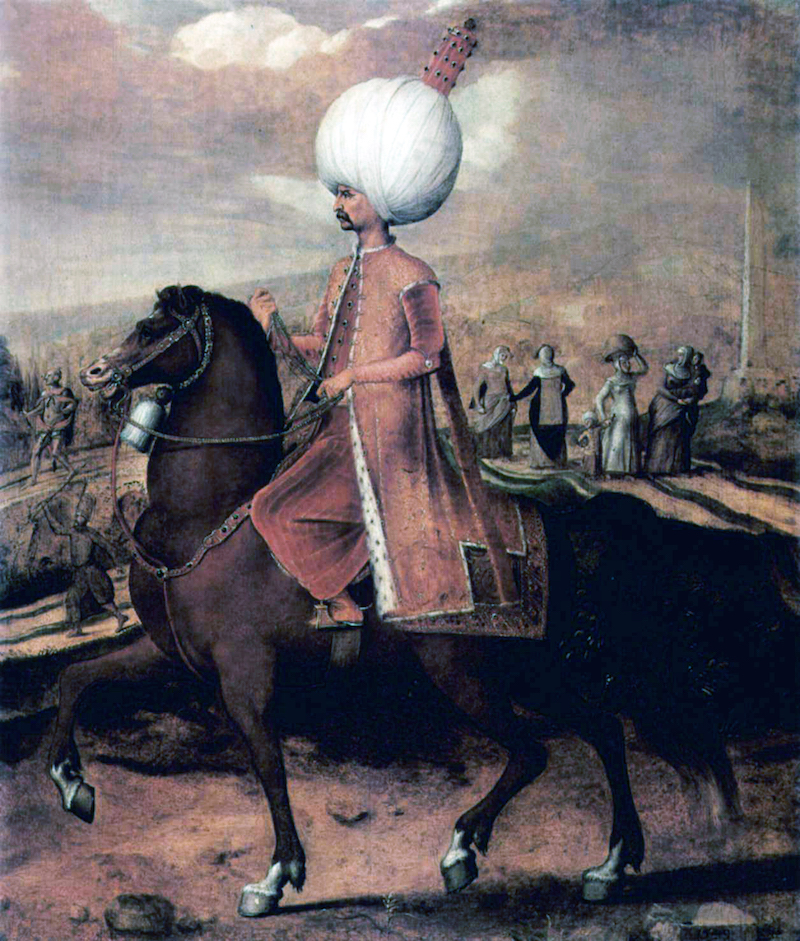

The exhibition shows, too, the interest of the Ottomans in Christian culture. Not only did Ottoman rulers regard themselves as heirs of Byzantium, but they treasured the talents and techniques of Renaisance artists. Sultans invited western artists, such as Giovani Bellini, to Constantinople (or Istanbul, as it became), to paint portraits and depict Ottoman life, as they would Western rulers and Western courts. The portraits of sultans, and of other leading figures in the Ottoman court, by Bellini and Veronese in particular, are quite striking.

There is a wide range of materials in the exhibition – paintings, maps, manuscripts, tapestries, weapons and scientific instruments. The great names of the Renaissance are here – Titian, Dürer, Tintoretto, Botticelli Bellini, Veronese. But what makes the exhibition so compelling is the excavating of lesser-known art from central and eastern Europe, in particular from Hungary and Poland, two countries in direct and close contact with the Ottoman empire, and whose relationship with the Ottomans is often ignored and yet, as this exhibition reveals, hugely important.

The Renaissance, as Şhafak writes,

is a wonderful place to start thinking about the distance between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’. As this exhibition so beautifully demonstrates, that distance has less to do with the world outside than with the world inside our minds.

Many thanks for the wonderful reproductions. Wish I could see the exhibition.

As a former early modern historian though, I must say that this “them and us”, “othering” and “demonisation” theme

is now being very much over-used, yielding much less of interest than its deployers claim. In particular, its deployers often use it breathlessly and comically righteously to suggest that it is opening up whole new insights – as if it had never occurred to earlier academic and popular historians that e.g. here, the Ottomans, were other than scary 2-dimensional “others”. The complicated history of Ottoman-Christian relations has pretty well never been treated in this simplistic way. It is no Saidian “revelation” that various Europeans at the time (from rulers, to nobles on the Grand Tour, or in the army, to clerics, to artists and writers etc..) saw the Ottomans through the lens of their own culture and various preoccupations, but were also often curious and open-minded…

Well, it would not really matter to have so many people using now rather hackneyed terminology to tell us what we already knew, and if this inspires interesting exhibitions, then it’s a plus. The problem is, though, that over-emphasis on “othering” (especially when there is often an irritating elision between the mere fact that people see differences from (and similarities to) others always through their own eyes and can..er…do no other, and “othering” seen as some deforming and sinisterly instrumental process) often tendentiously evaporates real history even as it pretends to be super-profound about it. Negative or positive “images” of “others” in history – e.g. art and literature – are investigated just for what they say about the image-maker or transmitter and his cultural agenda, as it were, and any other informational content of his testimony is sidelined. For example fear of “the Turk” even in Central/South-Eastern Europe – even as much of it was being invaded (!) – somehow gets repackaged as just some sort of cultural “othering” complex!

This is a fascinating article, but the problems I mention are rather well expressed, unwittingly, in the para:

“But what makes the exhibition so compelling is the excavating of lesser-known art from central and eastern Europe, in particular from Hungary and Poland, two countries in direct and close contact with the Ottoman empire, and whose relationship with the Ottomans is often ignored and yet, as this exhibition reveals, hugely important.”

“Lesser-known” to whom? Not, frankly, to people in Central/East Europe (I live in Czecho) or to any West European academic or popular historian dealing with the Ottoman Empire and its relationship to Christendom in the early modern period! Ignored by whom? Only by the sort of West European and other anglo- audiences for whom East European geography is hazy and East European history including the Ottoman invasions and incursions is more or less a blank. And no one informed would guess from the odd formulation “direct and close contact” with the Ottoman Empire, that much of Hungary was actually ruled by the Ottomans from 1541 to 1699!