Downtown Detroit looks almost like any other American city. Clusters of skyscrapers, huddles of cranes throwing up new high rises, expensive hotels with a dozens of valets lounging outside. Yet, look a bit closer, and you notice that in many of the blocks the windows are blacked over or broken, and bushes are growing on the ledges. Step outside the centre, and you find beautiful houses – standing in the middle of what appears like desolate fields. You spot kestrels perched atop broken streetlamps. You drive down streets where four or five buildings are standing and functioning, and then there’s a gap as the next have been demolished. And so it goes on, seemingly for miles.

Downtown Detroit looks almost like any other American city. Clusters of skyscrapers, huddles of cranes throwing up new high rises, expensive hotels with a dozens of valets lounging outside. Yet, look a bit closer, and you notice that in many of the blocks the windows are blacked over or broken, and bushes are growing on the ledges. Step outside the centre, and you find beautiful houses – standing in the middle of what appears like desolate fields. You spot kestrels perched atop broken streetlamps. You drive down streets where four or five buildings are standing and functioning, and then there’s a gap as the next have been demolished. And so it goes on, seemingly for miles.

But Detroit is not simply a city in decline. For every broken building there seems to be a shiny start-up. Crumbling churches converted into music hubs, a winery in the midst of a derelict row of buildings, and a bicycle shop almost everywhere you looked – how many bicycles, I wondered, do the people of Detroit need? There is something quite surreal in this inextricable combination of dereliction and hope, of decline and resurgence.

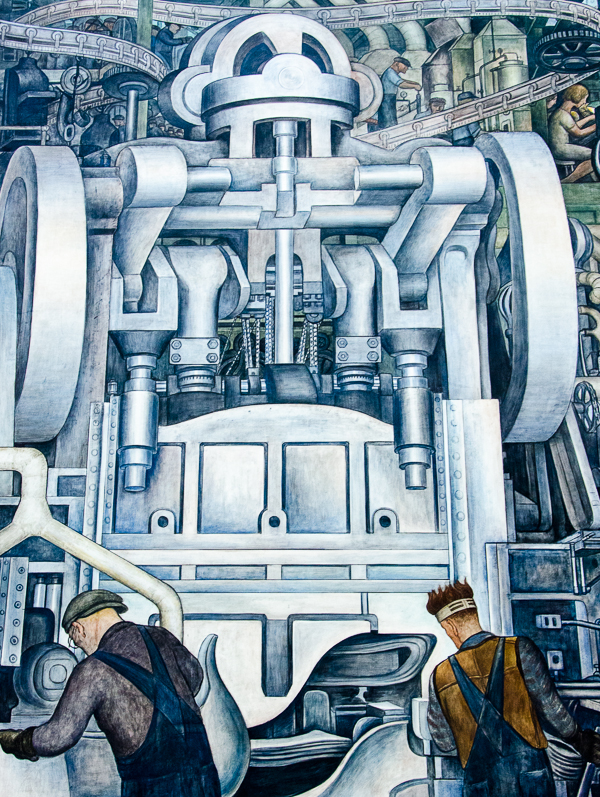

But what really links Detroit’s past to its present lies within the grand walls of the Detroit Institute of Art – a beautiful, imposing Beaux Art building built in the city’s heyday of the 1920s. Inside is one of the city’s great treasures – Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals, a magnificent work, for which alone it is worth travelling to Detroit.

Rivera was born in Guanajuato, Mexico, in 1886. His art reflected his political passions. Artistically, he was influenced both by modernism, especially Cubism and the works of Paul Cezanne, and by Renaissance frescoes. Politically, he was inspired by the Mexican and Russian Revolutions. In the years after the First World War, Rivera created on the walls of public buildings a series of murals about Mexico’s people and its history, marrying a modernist aesthetic with revolutionary aspirations and traditional Aztec themes. These were neither socialist realist propaganda, nor didactic works. Rather, they told stories with many layers of meaning, but always infused with a burning sense of anger at social injustice.

In 1931, Rivera was commissioned by Wilhelm Valentiner, director of the Detroit Institute of Art, to produce a series of murals on Detroit life. Born in Germany, Valentiner was sympathetic both to Rivera’s artistic approach and to his political philosophy. While still in Germany, he had helped create the Novembergruppe, a group of revolutionary artists who took their name from the failed German revolution of November 1918. Valentiner became director of the DIA in 1924 (a post he held for 21 years) and worked tirelessly to persuade the board, funders (primarily Edsel Ford, Henry Ford’s son and heir, who became both president of the Ford Motor Company and a major cultural benefactor in Detroit), and Rivera himself to create a major work that told the story of ‘the history of Detroit’ and of ‘the development of industry in this town’. What Valentiner eventually got was a masterpiece that told not only the story of industrial Detroit, but also fables much deeper and far richer than that of one city.

Rivera arrived in Detroit in April 1932. He spent three months researching Ford plants in the region, preparing hundreds of sketches and concepts for the mural. Beginning the paintings themselves in July, he completed the work in an extraordinary eight months.

The murals were created in the depths of the Great Depression. The month before Rivera arrived in the police and Ford company guards attacked a Ford Hunger March, shooting dead five workers. Five days later, 60,000 workers followed the funeral process. March 1933, when the murals were first shown to the public, was the worst month for joblessness in the history of America.

But Rivera’s murals were not primarily about suffering or the Depression. Rather they are explorations of human possibilities and of hope. Rivera had tremendous admiration for the industrial might and engineering skills that had created modern American cities, ‘In all the constructions of man’s past – pyramids, Roman roads and aqueducts, cathedrals and palaces – there is nothing to equal these’, he wrote.

In the Rivera Court – as the room in which the murals stand came to be known – two giant murals, each taking up the length of the north and south walls, depict the assembly lines at Ford’s Rouge plant in Detroit. Around these two centrepieces are 25 other smaller murals, whose themes range from ancient Aztec cosmology to modern science and technology. Taken as a whole, the murals explore the relationship between humanity, technology and nature, survey the ambiguous character of modern technology (symbolized by one panel depicting the creation of vaccines and another the creation of poison gas), depict capitalism as a force both for human advancement and human degradation (Rivera saw the assembly line as both a great leap forward and as a form of mortification), and delve into the relationship between the individual and the collective. None of these themes are presented didactically, but through the use of myth, symbol and a cat’s cradle of allusions across the various paintings. The Detroit Industry Murals constitute without doubt Rivera’s greatest work.

The opening of the murals to pubic viewing in March 1933 generated great controversy. Many found it shocking that Edsel Ford, a titan of American capitalism, should, in the midst of the Great Depression and at a time when thousands of workers were being laid off, pay a communist $20,000 to depict the lives of workers.

The murals themselves caused a scandal. An editorial in the Detroit News condemned them as ‘coarse in conception’, ‘foolishly vulgar’ and ‘un-American’. Clergymen lined up to denounce the work as ‘blasphemous’. Their ire was particularly stoked by a panel called Vaccination, which showed a child being inoculated by a doctor and a nurse. In the foreground are a horse, a sheep and a cow, in the background three scientists creating vaccines. The composition echoed Renaissance nativity scenes, with the doctor and nurse playing the role of Joseph and Mary, and the scientists the three wise men. ‘The painting should be washed from the walls, because it inevitably must impress the spectator as a satire of that family dear to religion’, thundered the Reverend H Ralph Higgins, senior curate of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The people of Detroit flocked to the murals. On one Sunday alone in March 1933, 10,000 people came to view Rivera Court. As Linda Park Downs observes in her wonderful history of the murals, ‘To automobile workers, who had never seen themselves depicted in a cultural institution of the city, it was a revelation.’

The controversy over the Rivera murals raged for decades. In the 1950s, at the height of McCarthyism, the DIA, to its shame, erected a sign above the entrance to Rivera Court that read:

Rivera’s politics and his publicity seeking are detestable. But let’s get the record straight on what he did here. He came from Mexico to Detroit, thought our mass production industries and our technology wonderful and very exciting, painted them as one of the great achievements of the twentieth century. This came after the debunking twenties when our artists and writers found nothing worthwhile in America and worst of all in America was the Middle West.

Rivera saw and painted the significance of Detroit as a world city. If we are proud of this city’s achievements, we should be proud of these paintings and not lose our heads over what Rivera is doing in Mexico today.

The irony, as the Wall Street Journal’s art critic was later to observe, was that a work by a Marxist inspired Mexican artist ‘remains one of America’s most significant monuments to itself’.

Eighty years on, the Detroit Institute of Art became once more a focus for great controversy. In 2013, the city of Detroit filed for bankruptcy, and with an estimated $18 billion debt, the largest municipal bankruptcy filing in US history. Creditors demanded that many of the DIA’s greatest jewels should be auctioned off to help pay the debt. That threat led to a huge campaign by locals, including by those whose pensions were imperilled, to campaign in defence of the Institute. Eventually the DIA persuaded private donors and benefactors to stump up more than $800 million to help save public workers’ pensions, in return for which museum was protected and came to be owned not by the city but by an independent charitable trust.

For many the argument over the sale of the Institute’s riches was simple. ‘It’s hard to go to a pensioner on a fixed income’, observed the state-appointed emergency manager Kevyn D Orr and say, “We’re going to cut 20 percent of your income or 30 percent or whatever the number is, but art is eternal.’ Or as critic Peter Scheldahl put it in the New Yorker, ‘Art will survive. The pensioner will not’.

But, as others pointed out, it was an argument that made little sense, economically or aesthetically. It was not the fact that the DIA had purchased its masterpieces that had caused Detroit to go bankrupt in the first place; nor would selling its Rembrandts and Picassos protect that pensioners’ incomes. A fire sale would leave untouched the economic and political developments, and the poor management and appalling practices, that had conspired to destroy the city.

Art is not something separate from our everyday existence. It is one of the tools through which we make sense of that existence. The worth of art lies not in the price that it can fetch at Sotheby’s or Christie’s but in the way that it develops our consciousness, enriches us spiritually, allows us to expand our vision even in the midst of great social dislocation and misery, makes us better understand how we have arrived at where we have arrived, enables us better to dissect the present and to think of the future.

That is what Diego Rivero’s magnificent murals remind us. And that is why they are as important today as they were eight decades ago.

The images are all details from Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals; photos taken by me.

Thank you, thank you for this wonderful post filled with samples of Diego Rivera’s mural. Rivera was a Mexican communist, by the way. Somewhat different from a European communist.

What remarkable murals! Thank you so much for this fascinating and informative post and for the pictures.

Wasn’t Diego Rivera implicated in a murderous attempt upon the life of Leon Trotsky whilst he was exiled in Mexico ?

These are fantastic. I now must find and see them.

I notice the only face shown clearly is that of boss.