The latest issue of Art Review carries, under the headline ‘The truth about “cultural appropriation”‘, an edited version of my recent talk on cultural appropriation at London’s Rich Mix. Here is an extract:

One of the key arguments of many such critics is that one speaks through one’s identity; that one speaks, as writer Nesrine Malik has put it, ‘as a’: ‘as a woman’, ‘as a Muslim’, ‘as an immigrant’. And those who are not ‘as a’ must take their cue from those who are, especially if they happen to be privileged by being white or male or straight. ‘Lived experience’, as Malik has put it, ‘is on its way to becoming the superior and most veracious form of truth.’ And as the novelist Kamila Shamsie has observed, ‘What started as a thoughtful post-colonial critique of certain types of imperial texts somehow became a peculiar orthodoxy that essentially denies the possibility of imaginative engagement with anyone outside your little circle.’

What is really being appropriated, in other words, is not culture but the right to police cultures and experiences, a right appropriated by those who license themselves to be arbiters of the correct forms of cultural borrowing. Such policing is deeply problematic, both artistically and politically. It deadens creativity and it assaults imagination. The importance of imagination is that we can take ourselves beyond where we are, beyond our own narrow perspectives, to imagine other peoples, other worlds, other experiences. Without the ability to do that, both artistic creativity and progressive politics shrivel.

Take the debate about Dana Schutz’s Open Casket (2016), a painting derived from photographs of the body of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old African American murdered by two white men in Mississippi in 1955. Till’s mother had urged the publication of photographs of her son’s mutilated body as it lay in its coffin. Till’s murder, and the photographs, played a major role in shaping the civil-rights movement and have acquired an almost sacred quality.

Schutz’s painting caused little controversy until it was included in the prestigious Whitney Biennial Exhibition in New York. Many objected to a white painter depicting such a traumatic moment in black history, and for that depiction to receive the accolade of a Whitney Biennial presentation. The British artist Hannah Black even organised a petition to have the work destroyed.

In the same Whitney Biennial was a painting by Henry Taylor titled The Times They Ain’t Changing, Fast Enough! (2017) which depicts the death of Philando Castile, an African American man horrifically shot dead in his car by a policeman, in 2016. Taylor’s painting, unlike Schutz’s, has received little criticism, but rather has been praised for its ‘hauntingly vivid depiction’ of the shooting of Castile.

In my view neither painting has significant artistic merit. For critics of cultural appropriation, however, the real difference is not aesthetic, but identitarian. Schutz is white and Taylor black. To subsume aesthetic considerations to those of identity is to render art meaningless. It is also politically troubling. The campaign against Schutz’s work, as the American critic Adam Shatz has observed, contains an ‘implicit disavowal that acts of radical sympathy, and imaginative identification, are possible across racial lines’. Or, as Shamsie tweeted (in response to the controversy over Lionel Shriver’s defence of cultural appropriation at last year’s Brisbane Writers Festival) ‘”You – other – are unimaginable” is a far more problematic attitude than “You are imaginable”.’

Many critics of cultural appropriation insist that they are opposed not to cultural engagement, but to racism. They want to protect marginalised cultures and ensure that such cultures speak for themselves and are not simply to be seen through the eyes of more privileged groups. The American critic Briahna Joy Gray acknowledges that ‘The idea that only black artists have the right to address Emmett Till’s murder through art seems wrong.’ But, she argues, critics of Dana Schutz ‘have a point’ about ‘exploitation’: ‘Depicting Till is not a problem but using Till to garner profit and acclaim would be.’

It is true that cultural engagement does not take place on a level playing field, but is shaped by racism and inequality. Racism ensured that the great black pioneers of rock ‘n’ roll never received their due, whereas many white artists, from Elvis Presley onwards, were feted as cultural icons. Yet, as the poet Amiri Baraka once observed, the issue here is not that of cultural appropriation at all: ‘The problem is that if The Beatles tell me that they learned everything they know from Blind Willie [Johnson], I want to know why Blind Willie is still running an elevator in Jackson, Mississippi. It’s that kind of inequality that is abusive, not the actual appropriation of culture because that’s normal.’

Preventing the Beatles from drawing on the work of Blind Willie Johnson or other black singers would have done little to improve black peoples’ lives. It would not have overthrown Jim Crow laws in the 1950s. It would not rid America of discrimination in the labour market today. Nor will preventing Dana Schutz ‘profiting’ from painting Emmett Till protect the Emmett Tills of today.

Only mass social and political campaigns to transform the very structures of society – such as the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s – can bring about such change. Otherwise, social justice comes to be seen not as the erasure of exploitative structures but merely as the possibility of ‘cultural fairness’ within them. The campaigns against cultural appropriation are an implicit acceptance that the playing field cannot be levelled, and that the best we can do is fence off certain areas.

Read the full essay in the Art Review.

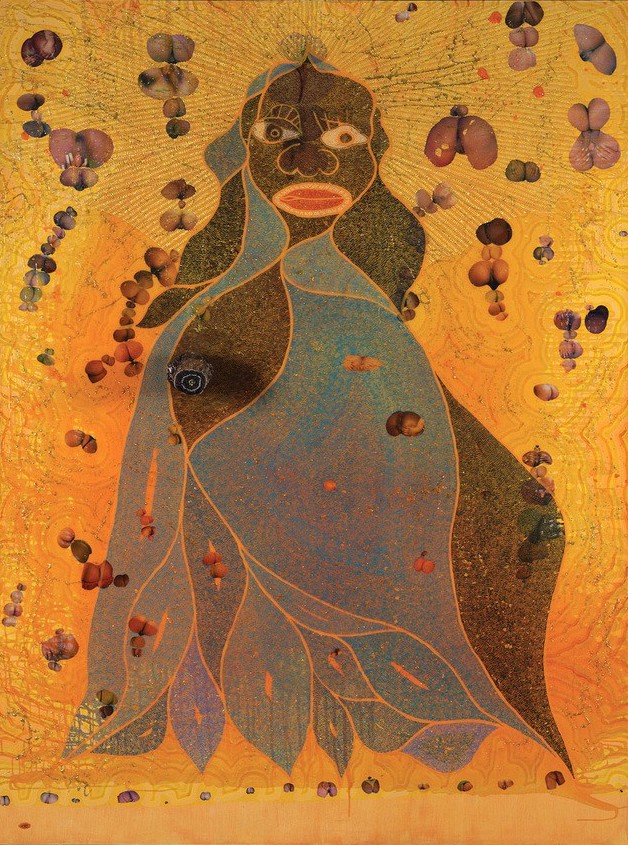

The painting is Chris Ofili’s ‘The Holy Virgin Mary’. (For the relevance of the painting for my argument you will have to read the full essay...).

Racism consists in a) dividing people into “races”, e.g. “blacks” and “whites” and then b) assigning different rights to them based on that classification. So denying a “white” painter the right to paint a certain topic while a “black” painter is allowed to do so is just an instance of racism itself.

If we start from a principle of equality of people we must not do b). If we don’t do b), then a) is unnecessary and useless.

To overcome racism, we have to stop thinking and acting in terms of racial distinctions. This also means that defining your “identity” in terms of racial concepts (e.g. defining yourself as a “black” person or a “white” person) is a very bad idea.

I am a member of an international family with some members from West Africa, some from East Africa, some from Europe and some from New Zealand. Some of us have ancestors in several areas. For example, my daughter has German and West African ancestors. But we don’t think of ourselves as being of different “races”. Why should we do so? For what purpose would such a distinction be useful? I need a stronger sun screen than my wife and a different type of comb, but for that, we don’t have to think of ourselves belonging to different races. Our bodies also differ in many other ways, so what is all that fuzz about skin color about? I also need a different type and strength of glasses, but that does not mean I belong into the “astigmatic” race and she into the “myopic” one. We don’t devide ourselves into groups with different rights depending on the type of glasses we are needing, so why should we divide ourselves into comb- or sunscreen-based types?

Thinking about us in terms of “race” is simply not useful for any purpose, so why do it? Racial distinctions have been invented to have a pretext for assigning different rights to different people in order to exploit some of them. If you say everybody has the same rights then why make such distinctions? They are unnecessary and have proved to be extremely destructive during the course of history. So let’s stop making such distinctions.

The problem is not that a “white” artist paints about a topic belonging to the “black” community; the problem is that the people who make that an issue are still distinguishing themselves and others into “blacks” and “whites”. This is an unwise thing to do. The Dana Schutz case demonstrates that you just get into racism if you do so. The problem cannot be overcome by defining racial identities each with their holy districts and taboos, but only by dissolving them completely.

We should also generally question the concept of “identity”. Why do we have to define ourselves as members of some separate group, instead of defining ourselves as individuals (and that is what “identity” should really mean).