This essay, a review of the BBC documentary The Satanic Verses: 30 Years On, was my Observer column this week. (The column included also a short piece on the use of predictive algorithms by local authorities.) It was published in the Observer, 3 March 2019, under the headline ‘The Satanic Verses is still creating monsters, even new book-burners’.

Sometimes, you just have to shake your head to clear it and look again. Did he really write that? So it was when I read a review in the Independent by Sean O’Grady of The Satanic Verses: 30 Years On, a BBC documentary on the Rushdie affair and its legacy.

But, yes, in the last paragraph, he really did write this:

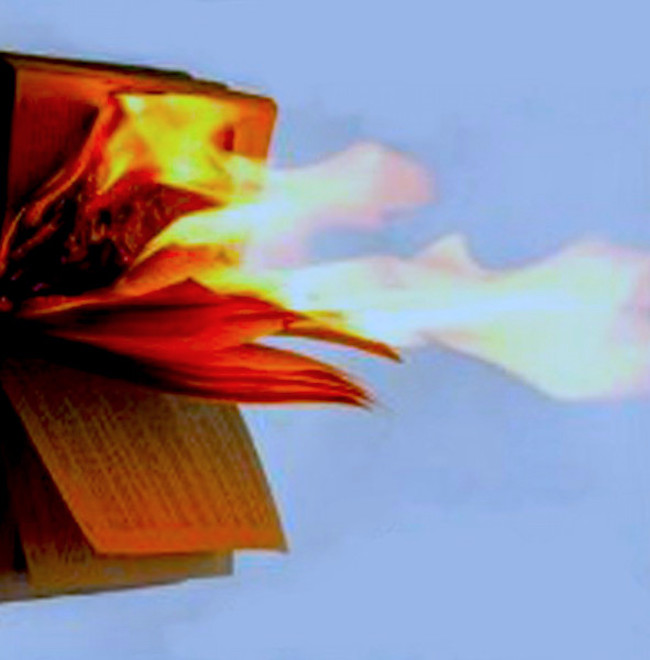

Rushdie’s silly, childish book should be banned under today’s anti-hate legislation. It’s no better than racist graffiti on a bus stop. I wouldn’t have it in my house, out of respect to Muslim people and contempt for Rushdie, and because it sounds quite boring. I’d be quite inclined to burn it, in fact.

Even in today’s censorious, don’t-give-offence climate, there is something startling in the casualness with which the associate editor of a national newspaper can proudly proclaim himself a would-be book-burner and book-banner.

The Satanic Verses: 30 Years On, presented by the broadcaster Mobeen Azhar, was an intelligent, subtle exploration of the impact of the Rushdie affair on Britain’s Muslim communities. Azhar was a child at the time of the fatwa. He returned to his Huddersfield primary school, remembering, with a nervous laugh, playground games of ‘How do we kill Salman Rushdie?’ The Satanic Verses was a ‘spectre’ that hung over his life then, he observed, and still haunts Muslims now.

It’s been a ghostly presence in my life, too. I am of the generation that came of age just before The Satanic Verses, a generation that was largely secular and as fierce in our condemnation of religious constraints as of racist bigotry.

I lost many friends over the Rushdie affair. Friends who were as irreligious and leftwing as I was, but who now celebrated book-burnings and chanted ‘death to Rushdie’. And, like Azhar in his documentary, I’ve spent much of my life mulling over that shift and its consequences.

The danger in looking at The Satanic Verses through the lens of the ‘Rushdie affair’ is that the novel comes to be seen simply as a fictionalised assault on Islam. It is, in fact, a dense exploration of the migrant experience, as savage in its indictment of racism as of religion.

The significance of the confrontation, however, as Azhar deftly draws out, lay less in what Rushdie wrote than in what the novel came to symbolise. There’s a scene in The Satanic Verses in which one of the central characters, Saladin Chamcha, is incarcerated in an immigration detention centre. The inmates have all been turned into monsters. ‘How?’ Saladin wonders. ‘They have the power to describe,’ comes the reply, ‘and we succumb to the pictures they construct.’

Rushdie was writing of how racism demonises its Others. He could equally have been describing the way the conflict over his novel created its own monsters.

The 1980s was a decade that saw the beginnings of the breakdown of traditional political and moral boundaries and the creation of new social terrains for which there was as yet no map or compass. It was a dislocation whose consequences we are confronting even now in the unstitching of politics.

Rushdie’s novels began charting this new terrain, capturing that sense of displacement. Ironically, one way to understand the anti-Rushdie campaign is as the first great expression of the fear of a mapless world, an outpouring of rage at the tarnishing of symbols of identity at a time when such symbols were acquiring new significance.

The battle over Rushdie’s novel had a profound impact not just on Muslim communities but on liberals, too, many of whom were as disoriented by the breakdown of boundaries, and equally sought solace in black-and-white certainties. Some saw in the Rushdie affair a ‘clash of civilizations’. For others it revealed the need for greater policing of speech in a plural society.

Thirty years on, both sentiments have become entrenched. We live in a world in which many view Muslims as the Other who don’t belong. And in which others want to ban – even burn – The Satanic Verses to ‘respect Muslims’.

Azhar had never read The Satanic Verses. Reading it now, he found some passages offensive. Yet, he insisted, ‘that does not mean I want to curb other people’s right to write things’. ‘As a community,’ he observed, ‘we need to be able to stomach debates about our culture and our religion, even if we find them offensive. Only when we can do that will the ghost of The Satanic Verses be put to bed.’

It’s not just Muslims who could do with heeding such wisdom.

My father told me that he knew a Christian preacher who would sometimes write in the margin of his sermon notes”Shout here, the argument is weak”. Similarly, resorting to extremes, causing disturbances and burning books would suggest the perpetrators have little rational arguments to use against the views expressed in the book.

Sean O’Grady was heavily criticised in the comments under that Independent piece, and so he should be, but apart from a few voices like Kenan here, and another one I saw in the Telegraph, it’s the sort of thing that can get pretty much ignored.

On the wider Rushdie affair, I can’t help thinking that that was always one of the possible forks in the road that our fledgling multicultural society might take. Thirty years ago, there were other possibilities at the time, and the Muslim communities were smaller and newer. I think the building up of numbers and the continual renewal from the Indian Subcontinent, prevented full integration from taking place and that there would have been a tension between the possible futures for Muslims in the U.K. For greater secularisation and integration, or for parallel societies to start forming.

The Satanic Verses was “an opportunity” perhaps, for the forces of reaction to make their move.

There were enough of them now to start insisting for “their” rights. And that meant, no more insults to their religion would be tolerated. And I’m also presuming, that cultural practices like cousin marriage and moving into heavily Muslim areas of towns and cities went ahead full steam also. After all, this was just taking advantage of the rights and freedoms that becoming British offered. You didn’t need to become like the British and integrate with them, any more than you chose to.

And just something I noticed online yesterday in Australia. An Egyptian called Sheik Omar Abdel Kafi is on a speaking tour of mosques in Australia. Apparently, he denies any Muslim involvement in 9/11 or the Charlie Hebdo attacks ….. and if that’s true, you have to wonder why mainstream mosques invite such people to come and speak to their congregations. This sort of thing happens all the time, but journalists like Sean O’Grady don’t pay it any attention. They’d be more upset about someone like Milo Yiannopoulos getting a visa to visit Australia.

I remember how angry many people were in Australia after the bomb at the Bali nightclub killed loads of Australians and they found out that the spiritual leader of the Indonesian terrorist group behind the bomb had also toured Australia, speaking at mosques there.

You could call this “post-Rushdie multiculturalism” – where sections of society weren’t even trying to integrate into their host societies any more. Or reserved the right to pick and choose the bits they wanted and the bits they rejected.

How could the once great Independent have fallen to such a dire state! I have my copy of The Satanic Verses, one book I would never lend, I always say, “go buy your own”!

Thank you, Kenan, for reminding us that the origins, as it were, of the crisis in liberal thinking comes from the Fatwa and those turbulent 80’s. Watching the unraveling of the Post WW2 world that gave hundreds of millions of people around the planet, for the first time ever, the possibility of autonomy and dignity, it is easy to despair. If we do not learn from the present times because we are too close to it AND if we do not learn from the past because we have already closed our minds to it- how then are we, the celebrated Homo-Sapiens (Wise humans) going to learn at all?

You sound dispirited in this article, which doesn’t surprise me. Deep down, you know the truth: Rushdie is a coconut, brown on the outside, white on the inside. That is why his brilliant but perverted novel is far more appealing to whites than it is to communities of colour. He could have used his talent to advance the anti-racist and anti-Islamophobic cause. Instead, he became an icon for Christopher Hitchens and similar fetishists of the Enlightenment.

I am of the generation that came of age just before The Satanic Verses, a generation that was largely secular and as fierce in our condemnation of religious constraints as of racist bigotry.

Exactly! Rushdie’s novel was an expression of, and invitation to, racial bigotry, which is why you found, and find, yourself in a minority in supporting it. The documentary made this clear: the Muslim community do not want Rushdie and other Islamophobes to have the ability or the right to insult them and their deepest-held beliefs. You and other Enlightenment-fetishes have literally had decades to make the case for “free speech” to the Muslim community and other communities of colour. You have failed. That should tell you something.

Sean O’Grady, in refreshing contrast, does not presume to know better than communities of colour. Good for him. However, I strongly disagree with his use of the phrase “Rushdie’s silly, childish book”. He hasn’t even read it (“it sounds quite boring”), so he’s obviously trying to suck up to Islamist reactionaries. Much of the tragedy of The Satanic Verses affair would disappear if Rushdie were not such a talented writer and The Satanic Verses not such a flawed masterpiece.