This is a transcript of a talk I gave at the Bristol Festival of Ideas, 21 May 2019, as part of the Coleridge Series.

‘Who has the right to speak?’ It is the key question in debates around free speech. Who should be allowed to speak? What should be permitted to be said? And who makes the decision?

Historically, the issues were relatively clear. Censorship was imposed from the top. Its aim was to deflect, contain or deem illegitimate any challenge to power.

Today, the issues seem less straightforward. Censorship still exists in the traditional sense of shielding those in power from challenge. Increasingly, however, much censorship today, particularly in liberal democracies, is imposed in the name of protecting not the powerful but the powerless or the vulnerable: laws against hate speech, for instance, or restricting the scope of racists or bigots.

This has created confusion and debate, particularly on the left. Where once the left was clearly opposed to censorship, now many support restrictions in the name of the progressive good. As the left has vacated the ground of free speech, the right, and the far-right, have become encamped upon it. Their attachment to freedom of expression is illusory and hypocritical. But this has further distorted the debate because the cause of free speech has come to be seen as the property of the right and the far-right, and made many liberals, and many on the left, even more hostile to the idea of free speech.

What I want to do today is to address some of these issues. And I want to do so by looking at three different arenas of censorship: state censorship; corporate censorship; and, finally, moral censorship or self censorship. In doing so I hope to show that the more we restrict the right of people to speak, even of those whose views we abhor, the more we undermine our own rights, too.

1

State censorship is the traditional form of censorship: restrictions on speech, from blasphemy to sedition, imposed by authority, largely to shield itself from challenge to authority. Such restrictions remain important weapons in curtailing speech in the contemporary world, especially in authoritarian or theocratic states – China, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Cuba, Zimbabwe. There are also, however, new forms of state censorship, particularly within liberal democracies, that express the changing contexts of contemporary debates about free speech. I want here to look briefly at two very different expressions of such new forms of state censorship that are important in Britain: censorship in the name, on the one hand, of the war on terror and, on the other, of the battle against hate speech.

Some of the most insidious forms of state censorship, yet ones which are barely talked, or even known, about, are those that derive from the government’s anti-terror strategy. I’m going to concentrate on one aspect of that strategy called Prevent, which is the government’s anti-radicalization programme. Prevent is one part of Contest, the UK government’s counter-terror strategy that was launched in 2004 by the then Labour government, and to which there have been a series of revisions over the past 15 years. The aim of Prevent is to counter terrorist ideology and the process of radicalization.

Its language is that of ‘safeguarding’, in the manner of policy to prevent child sexual grooming. ‘The purpose of Prevent’, according to the official strategy document, ‘is… to safeguard and support vulnerable people to stop them from becoming terrorists.’ In reality, what Prevent has created is a process of mass surveillance, a climate of suspicion, and censorship, both direct and indirect.

Prevent places a legal duty on public bodies such as universities and the NHS to identify in individuals early warning signs of radicalization and to report them. Such signs, according to official guidelines, include changing one’s ‘style of dress or personal appearance’ or using ‘derogatory names or labels for another group’. What might be seen in a different context as experimentation or obnoxiousness becomes seen in the context of Prevent as signs of terrorist sympathy, especially if you are Muslim.

The wrong kind of political interest is also a warning light. Curiosity about Palestine is, according to leaked teacher training materials, another sign of radicalization.

Last year more than 7300 people were referred under the Prevent process, almost half of them Muslims; fewer than 1 in 5 were referred to a so-called Channel panel that discussed their potential radicalization and of these in fewer than 1 in 3 cases was any further action taken. In other words, just 5% of those originally referred to Prevent may actually have even tenuous terrorist sympathies. In the process, what has been created is a deep-rooted climate of suspicion, a climate of suspicion that led to a 4-year-old boy being referred because when he said ‘cucumber’ the teacher thought he said ‘cooker bomb’. It’s worth asking what kind of society it is in which a toddler mispronouncing the word ‘cucumber’ comes to be regarded as a potential terrorist threat?

At universities, the issues run even deeper. Prevent, as the NUS’s Ilyas Nagdee has observed,

fundamentally alters the relationship between students and educators, with those most trusted with our wellbeing and development forced to act as informants… Normal topics that are discussed as a matter of course in our educational spaces are being treated as criminal

The Glasgow School of Art censored a work by one of its students, James Oberhelm, due to be shown as part of a Master of Fine Art exhibition. About war, and in particular war in the Middle East, it was censored apparently because it included an ISIS vIDEO.

Reading University flagged up as ‘security sensitive’ under Prevent guidelines an essay on the ethics of socialist revolution by the late Marxist academic Norman Geras. Students were warned not to access it on their personal devices, to read it only in a secure setting, and not to leave it lying around where it might be read by those not on the course. Tutors at other universities have been warned not to put on any reading list Milestones, a historically significant book written by Sayyid Qutb, the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, because it might ‘encourage radicalisation’. A criminology lecturer passed her list by the police to ensure that it was Prevent-safe. ‘We are entering a situation where thought becomes dangerous‘, observed Alison Scott-Baumann, professor of society and belief at SOAS.

Prevent also defines the kinds of speakers it is possible to invite to universities. Martin McQuillan, pro vice-chancellor at Kingston University, has talked of a ‘proscribed list of speakers that no one is willing to admit exists’.

Earlier this year, the Court of Appeal ruled that Prevent duty guidance to universities on inviting controversial speakers is unlawful because it is unbalanced, not sufficiently taking into account the requirements of freedom of speech. There is rightly much debate about no platforming at universities. Yet the kind of no-platforming that is imposed by Prevent is rarely discussed.

The impact of Prevent is felt not only through direct censorship but also through the creation of a broader climate of self-censorship, in which certain topics or issues or ideas or arguments are simply off limits. Gavin Barber, of Oxford Brookes University, told the annual conference Association of University Administrators in 2016 that some staff were now apprehensive even about approving the potentially controversial titles of master’s dissertations.

Muslim students in particular both have to self-censor and are protected by academics from subjects that might be deemed problematic. In the words of SOAS’s Alison Scott-Baumann, Prevent

means that some people can speak freely and some can’t. So if you’re a person of colour or you wear clothes that make it look like you might be Muslim, then you are regarded as possibly needing to be prevented from being radicalised and this means ‘protecting’ you from discussion of complex international situations.

Prevent is rarely brought into the conversation about state censorship. It should be. For it is a mechanism by which ‘Safeguarding’ becomes a means of stigmatizing and censoring, a process by which the state decides who has the right to speak, and what they have the right to speak about.

The second area of state censorship I want to look at is that of hate speech. Many, perhaps most, nations in the world proscribe hate speech. Few people – and I would imagine nobody here – would deny that hate speech is pernicious and needs to be challenged. The debate around hate speech is, however, about how best to do so, and what are the consequences of hate speech laws.

The argument that we should censor speech to prevent bigotry raises a number of questions. The first is about who decides what should be censored.

In January 2006, Iqbal Sacranie, then the secretary general of the Muslim Council of Britain, made some derogatory comments on Radio 4’s Today programme about homosexuality. The Metropolitan Police launched an investigation into whether Sacranie’s comments constituted ‘hate speech’.

In response to the police investigation, 22 imams and Muslim leaders wrote to The Times demanding the right to be able to ‘freely express their views in an atmosphere free of intimidation or bullying’. They added that ‘We cannot truly claim to be a free and open society while we are trying to silence dissenting views’.

Many of those same leaders had called for Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses to be banned. All had wanted the Danish cartoons, published just four months before Sacranie’s comments, to be censored.

The kind of hypocrisy, or moral blindness, expressed by those Muslim leaders is widespread, and far from limited to Muslims. Many of those happy to see cartoons lampooning Mohammed draw the line at anything mocking the Holocaust. Many gay rights activists want Muslims to be prosecuted for homophobia but want the right to criticize Muslims as they see fit. Racists such as Nick Griffin or Tommy Robinson want to be free to spout racist abuse but want Muslim clerics locked up for doing the same. And so it goes on.

We can see this today in debates around transphobia and anti-Semitism. Bigotry against trans men and women, and against Jews, is real, pernicious and needs challenging. At the same time, however, charges of transphobia and anti-Semitism are also used to curtail debate, delegitimize certain views and try to silence certain individuals with critical views.

The problem of censoring bigotry is not simply the difficulty in defining what it is that should be censored. It is also that the consequence of such censorship is not what many believe it to be. Banning certain forms of speech does not reduce or eliminate bigotry. It simply festers beyond the public gaze.

Sheffield University social geographer Gill Valentine has spent years researching the impact of speech bans. Restrictions, she shows, do not reduce bigotry but rather ‘change its form’ and ‘privatize’ it. ‘The privatized nature of contemporary prejudice’, Valentine argues, ‘makes it more difficult to expose and challenge, producing a frustration that offenders are “getting away with it”, and making it harder to identify patterns of prejudice in form and intent.’

The third, and perhaps most important, issue is that hate speech laws and restrictions may create obstacles for bigots but they can also serve to criminalize those challenging bigotry and injustice. The 1965 Race Relations Act introduced Britain’s first legal ban on the incitement of racial hatred. Among the first people convicted under its provisions was the Trinidadian Black Power activist Michael X, sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment in 1967, and four members of the Universal Coloured Peoples’ Association convicted for stirring up hatred against white people at Speakers’ Corner.

In the 1960s and 1970s, incitement laws were often used to target black activists whose views were regarded as unacceptable or dangerous. Today, those with unacceptable Muslim or Islamist views are more likely to be targets, from Samina Malik (the so-called ‘lyrical terrorist’) to protestors against the Danish cartoons, who were jailed for up to six years for chants that ‘solicited murder’ and ‘incited racial hatred’. Many countries now use hate speech laws to outlaw support for the anti-Israel BDS movement.

When the state gets to criminalize dissenting speech, even if it is bigoted, minorities themselves too often suffer.

2

The second arena of censorship that I want to explore is that of corporate censorship. Censorship has always been a tool of business, both direct censorship through, say, the enforcement of Non-disclosure Agreements, or NDAs, an issue that has been much in the news recently, or the wielding of libel laws; and indirect censorship through exploiting the social power that capitalists possesses to shape public discussion, for instance through the ownership of media companies, or through their ability to bribe or to finance politicians and institutions.

I want here to look briefly at a very contemporary debate about the relationship between global business, social power and censorship: that in relation to social media. In the early years, people held almost utopian view of the internet, and of social media, as democratic platforms, the means through which every one of us can enter into global conversations, and effect social change. More recently we have come to fear its dystopian consequences.

A handful of global companies – Google, Facebook, Twitter – control social media and possess enormous power over lives and our data. And social media itself has come to be seen as a platform not just for enabling social change but also for promoting cruelty and deceit: from fake news to misogynistic trolling, from the viciousness of 8chan forums to the insidious encouragement of self-harm on Instagram.

The consequence has been a set of contradictory attitudes towards tech companies. On the one hand, we worry that they possess too much power and are too invasive of privacy. On the other hand, we think that they should do more to clean up social media, to remove fake news, or restrain far-right trolls, or censor offensive messages. But the demand for greater policing of social media is really a call to put even greater powers in the hands of tech giants and to afford them even greater control over our lives.

Consider the issue of fake news that has become a major political controversy in recent years. There is, in fact, nothing new in panics about fake news. Before Facebook, there was the coffee house. In the 17th-century, panic gripped British royal circles that these newly established drinking salons had become forums for political dissent. In 1672, Charles II issued a proclamation ‘to restrain the Spreading of False News’ that was helping ‘to nourish an universal Jealousie and Dissatisfaction in the minds of all His Majesties good subjects’.

If there is a long history to fears about fake news, there is a long history to fake news itself, too. From the publication in 1920 in the Dearborn Independent, a newspaper owned by Henry Ford, of a series of articles about a global Jewish conspiracy based on the forged ‘Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion; to the publication in 1924 in the Daily Mail, four days before a general election, of the forged Zinoviev letter, a supposed directive from Moscow to British communists to mobilise ‘sympathetic forces’ in the Labour party; to the lurid media campaign in the 1980s against Winston Silcott, a black man convicted of the murder of PC Keith Blakelock during the Broadwater Farm riots, but released after three years when it was shown that the police had forged their interview notes; to the stories invented by the police and the Sun newspaper to damn Liverpool supporters after the Hillsborough tragedy in 1989; to the stories about Saddam Hussein’s nonexistent weapons of mass destruction that filled newspaper pages across the world in 2003, in the run-up to the Iraq war….

The list is endless. Lies masquerading as news are as old as news itself.

What is new today is not fake news itself but the purveyors of such news. In the past, only governments, major institutions and powerful figures could manipulate public opinion. Today, it’s anyone with internet access.

Instead of the carefully curated fake news of old, there is now an anarchic outflow of lies. What has changed, in other words, is not that news is faked, but that the old gatekeepers of news have lost their power. Just as elite institutions have lost their grip over the electorate, so their ability to act as gatekeepers to news, defining what is and is not true, has also been eroded.

There is another change, too. In the past, those with power manipulated facts so as to present lies as truth. Today, lies are often accepted as truth because the very notion of truth is fragmenting. ‘Truth’ often has little more meaning than ‘This is what I believe’, or ‘This is what I think should be true’. On issues from Brexit to same-sex marriage, all sides cling to their view as the truth, refusing to engage with ‘alternate’ views. As Donald Trump has so ably demonstrated, the cry of ‘fake news’ has become a way of dismissing inconvenient truths.

Against this background, we should be wary of the some of the solutions proposed to tackle the problem of fake news. For the aim of many such solutions is less about ridding ourselves of untruths than about restoring more acceptable gatekeepers – to allow governments or corporations to define what is and isn’t news or truth.

In May, Singapore passed a new law against fake news that require online media platforms to carry corrections or remove content the government considers to be false, with penalties including prison terms of up to 10 years or fines up to S$1m. Any minister can declare any fact to be false and order a correction. Singapore’s government, as Human Rights Watch observed, ‘wants to be the arbiter of what anyone can say about Singapore anywhere in the world’. Singapore is not the only authoritarian state to impose such laws – a host of others from Russia to Thailand to Vietnam have done so, too.

It’s not just authoritarian states that should worry us, but liberal democracies, too. France and Germany, for instance, have introduced laws banning fake news online. Other Western states are considering similar legislation. Giving the state the right to define what is truth is troubling whether that state is authoritarian or democratic, whether reactionary or liberal.

And it is not just governments that have become the arbiters of truth. For what fake news laws do is to allow, or to force, Facebook and Google and Twitter, and other global companies, pre-emptively to remove content, and turn the likes of Mark Zuckerberg into the gatekeepers of what constitutes ‘real news’.

The question we need to ask ourselves is, ‘Do we really want to rid ourselves of today’s fake news by returning to the days when the only fake news was official fake news?’ The point is not that fake news is not a problem that needs addressing. It is rather that the solutions now proposed are often more damaging than the problem itself.

Similar arguments can be made about the demand that tech companies police social media to censor bigots. I don’t have the time to discuss this in detail, but what I would say is that just as worries over fake news have helped turn Mark Zuckerberg into a gatekeeper of what constitutes ‘real’ news, so worries about hate speech have made Facebook and Twitter the moral arbiters of acceptable online discussion.

And just as hate speech laws end up being used against those fighting racism or bigotry, so do social media bans. Black activists in America continually have their posts taken down and are often banned because their critiques of racism are themselves deemed racist.

When Liam Neeson recently confessed to having once roamed the streets of east London hunting for black men to bludgeon with a baseball bat after a friend told him that she’d been raped by a black man, the American teacher and activist Carolyn Wysinger wrote on Facebook

White men are so fragile and the mere presence of a black person challenges every single thing in them.

Within 15 minutes Facebook had deleted her post as hate speech. And she was warned if she posted it again, she’d face a temporary ban. Such actions by Facebook have in fact become so common that African American activists even have name for it: Getting Zucked.

It’s a process of which we should all be wary. Speech bans don’t simply limit speech we abhor. Once you allow the state or corporations to police our speech, we can all get Zucked.

3

The final arena of censorship I want to look at is that of moral censorship or self censorship. Self-censorship is, of course, something that we all practice to a degree. Most of us do not simply blurt out every thought that comes into our heads, and most of us seek to keep debates civil and polite. Without constant editing, neither coherent thought nor rational conversation would be possible.

What I talking about here, however, is not such forms of self-editing that makes thinking and talking possible. It is rather political censorship that we have come to view as if it were a form of the essential self-editing necessary for thought and conversation. Iit’s a form of moral censorship because it is a rooted in a belief that has taken hold over the past 30 years that it is morally necessary to refrain as far as possible from giving offence to other peoples or cultures.

Last month the Saatchi Gallery in London covered up two paintings by the pseudonymous artist SKU. The paintings incorporated an image of a nude and included the text in Arabic of the shahada , the Islamic declaration of the oneness of God and of Muhammed as God’s messenger. A Muslim visitor to the gallery complained that it was blasphemous.

It was the artist SKU who suggested covering up the paintings. It was, he said, ‘a respectful solution that enables a debate about freedom of expression versus the perceived right not to be offended.’ Except that in covering up the paintings, the debate was already settled, and in favour of those who demand censorship.

That covering up a painting should be seen not as what it is – the acceptance that one should not be blasphemous or give offence – but rather as ‘a respectful solution that enables a debate about freedom of expression’ expresses a fundamental shift that has taken place over the past three decades – the acceptance as a mainstream liberal view of the idea that it is wrong to give offence to other cultures or peoples.

At the heart of the argument for censorship as progressive, and of the giving of offence as a moral wrong, is the belief that a plural society places particular demands on speech, and that speech must necessarily be less free in such a society. For diverse societies to function and to be fair, so the argument runs, we need to show respect not just for individuals but also for the cultures and beliefs in which those individuals are embedded and which helps give them a sense of identity and being.

This requires that we police public discourse about those cultures and beliefs both to minimise friction between antagonistic cultures and beliefs and to protect the dignity of those individuals embedded in them. As the eminent Bristol sociologist Tariq Modood has put it, that ‘If people are to occupy the same political space without conflict, they mutually have to limit the extent to which they subject each others’ fundamental beliefs to criticism.’

I take the opposite view. It is, in my view, precisely because we do live in plural societies that we need the fullest extension possible of free speech. In plural societies, it is both inevitable and important that people offend the sensibilities of others. Inevitable, because where different beliefs are deeply held, clashes are unavoidable. Almost by definition such clashes express what it is to live in a diverse society. And so they should be openly resolved than suppressed in the name of ‘respect’ or ‘tolerance’. And important because any kind of social change or social progress means offending some deeply held sensibilities. Or to put it another way: ‘You can’t say that!’ is all too often the response of those in power to having their power challenged. To accept that certain things cannot be said is to accept that certain forms of power cannot be challenged.

The notion of giving offence suggests that certain beliefs are so important or valuable to certain people that they should be put beyond the possibility of being insulted, or caricatured or even questioned. The importance of the principle of free speech is precisely that it provides a permanent challenge to the idea that some questions are beyond contention, and hence acts as a permanent challenge to authority. This is why free speech is essential not simply to the practice of democracy, but to the aspirations of those groups who may have been failed by the formal democratic processes; to those whose voices may have been silenced by racism, for instance.

The real value of free speech, in other words, is not to those who possess power, but to those who want to challenge them. And the real value of censorship is to those who do not wish their authority to be challenged. The right to ‘subject each others’ fundamental beliefs to criticism’ is the bedrock of an open, diverse society. Once we give up such a right in the name of ‘tolerance’ or ‘respect’, we constrain our ability to challenge those in power, and therefore to challenge injustice.

All of which takes us back to the question ‘Who has the right to speak?’

One can answer this from both a normative and a social perspective – Who should be able to speak? And who actually gets to speak?

From a social perspective, many are excluded or denied the right to speak: those who don’t have the social power to make their voices heard, those who through racism or misogyny or homophobia are denied access to public space, those who are regarded as a threat to the existing power relations. And certain individuals and groups have privileged access to the media.

This has led many to insist that from a normative perspective, certain people should be excluded from having the right to speak, that certain political or moral views should be prohibited too. That those individuals whose bigotry makes it more difficult for women or minorities or oppressed groups to enter public space or to join the conversation, and those views that call for discrimination or hatred, should be barred. Hence the demand for hate speech laws, for laws outlawing blasphemy or restraining the giving of offence, for restrictions on the alt-right, for the closing down of social media accounts of bigots and trolls, and so on.

I understand the reasons why people make those demands, and what motivates them to do so. But, I hope, I have questioned the cogency and consequences of such arguments, and shown why it is those without power who most suffer from censorship and restriction on speech.

I have always argued that it is morally incumbent on those who defend free speech also to take a stand against bigotry and hatred wherever it reveals itself. But I would also argue that it is incumbent on those who challenge bigotry also to defend free speech. To enable censorship is to furnish new weapons that can be used against the powerless and the vulnerable. It is those with power and the need to wield censorship who are able to do so. It is those whose most potent weapon is their voice and their argument who most require free speech.

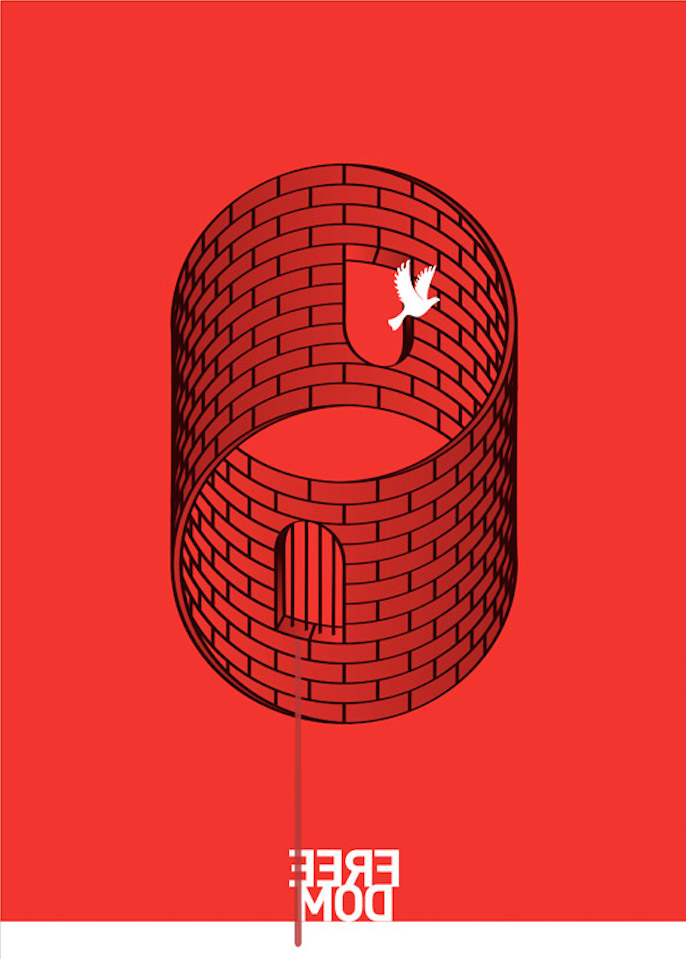

The images are all from a ‘Posters for Tomorrow’ competition on freedom of expression.

A recent example; the failure of articles about Emil Nolde and his relationship with the Nazis to show his viciously anti-Semitic * Martyrdom*, in which a contemporary Jewish couple gloat at the spectacle of Christ crucified in the background. How is rational discussion of the subject even possible if we are not presented with such crucial evidence?

Yes, I know it’s offensive, because I was offended by it. I am 80, Jewish, and had to walk out of a gallery where it was on display. That’s not the point.

Mark Twain said (paraphrase):

You should respect the other man’s beliefs, but only in the same sense that you respect his opinion that his wife is beautiful and his children are well behaved.