The latest (somewhat random) collection of recent essays and stories from around the web that have caught my eye and are worth plucking out to be re-read.

European policies create new dangers on Mediterranean

Steffen Lüdke, Maximilian Popp,

Jan Puhl & Raniah Salloum,

Spiegel International, 18 June 2019

For refugees, Europe is increasingly becoming a fortress without a gate. Even volunteer maritime rescuers are now being criminalized. Ports are closed to them. Ships are confiscated. Helpers are put on trial. Lifeline captain Claus-Peter Reisch was just sentenced to pay 10,000 euros by a Maltese court because his ship hadn’t been properly registered. The Italian Public Prosecutor’s Office is accusing 10 volunteers from the vessel Iuventa of illegal immigration. The crew could face up to 20 years in prison.

With their blockade policy, the Europeans have decimated the flotilla of private maritime rescuers, which at one point included as many as 12 ships. Now, on many days, not a single rescue ship can be found patrolling the waters between Europe and North Africa.

The EU completely ceased maritime rescues in the fall. It merely monitors the sea from the air and cooperates with the Libyan coast guard, which has expanded its search zone since 2017. The Libyan ships capture refugees near their own coast and bring them back to the country, which is in the midst of a civil war. They place them in camps, where many are tortured, raped or, in some cases, forced to become soldiers.

The EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights guarantees protection to people who are fleeing from war or political persecution. But the EU member states have, in practical terms, eliminated it. They have sealed their borders, expelled refugee helpers and erected fences. They pay autocrats like Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to prevent migrants from continuing their journey…

When several hundred refugees drowned in a shipwreck near Lampedusa in 2013, it still triggered outrage among European leaders and prompted the EU to invest in rescue programs. But now the EU member states are willing to accept the disasters as collateral damage. Many Europeans are outraged about the wall U.S. President Donald Trump wants to build at the border to Mexico, even as they are sealing themselves off from immigration in ways that are even more brutal than what the Americans are doing. On Thursday and Friday of this week, EU leaders will meet at a summit in Brussels where they will determine their policy agenda through 2024. It is unlikely that the EU is going to undertake any kind of fundamental course correction. In terms of EU asylum policy, the desire to keep migrants far away – no matter how – has been the imperative for some time now.

Read the full article in Spiegel International.

I helped save thousands of migrants from drowning.

Now I’m facing 20 years in jail

Pia Klemp, Newsweek, 19 June 2019

In today’s Europe, people can be sentenced to prison for saving a migrant’s life. In the summer of 2017, I was the captain of the rescue ship Iuventa. I steered our ship through international waters along the Libyan coastline, where thousands of migrants drifted in overcrowded, unseaworthy dinghies, having risked their lives in search of safety. The Iuventa crew rescued over 14,000 people. Today, I and nine other members of the crew face up to twenty years in prison for having rescued those people and brought them to Europe. We are not alone.

The criminalization of solidarity across Europe, at sea and on land, has demonstrated the lengths to which the European Union will go to make migrants’ lives expendable.

Two years ago, Europe made renewed efforts to seal the Mediterranean migrant route by draining it of its own rescue assets and outsourcing migration control to the so-called ‘Libyan Coast Guard’, comprised of former militia members equipped by the EU and instructed to intercept and return all migrants braving the crossing to Europe. NGO ships like the Iuventa provided one of the last remaining lifelines for migrants seeking safety in Europe by sea. For European authorities, we were a critical hurdle to be overcome in their war against migration…

None of us facing charges for solidarity is a villain, but neither are we heroes. If it is alarming that acts of basic human decency are now criminalized, it is no less telling that we have sometimes been lauded by well-intentioned supporters as saints. But those of us who have stood in solidarity with migrants have not acted out of some exceptional reserve of bravery or selfless compassion for others. We acted in the knowledge that the way our rulers treat migrants offers a clue about how they would treat the rest of us if they thought they could get away with it. Politicians who target, scapegoat and exploit migrants, do so to shore up a violent, unequal world—a world in which we, too, have to live and by which we, too, may be disempowered.

The criminalization of solidarity today is not only about stripping Europe’s most precarious of their means of survival. It is also an effort at foreclosing the forms of political organization that alliances between Europeans and migrants might engender; of barring the realization that in today’s Europe of rising xenophobia, racism, homophobia and austerity, the things that migrants seek—safety, comfort, dignity—are increasingly foreclosed to us Europeans as well.

Read the full article in Newsweek.

How France is persuading its citizens to get vaccinated

Alex Whiting, Mosaic, 19 June 2019

One in three French people think vaccines are unsafe – the world’s highest rate – and nearly one in five believe they aren’t effective – second only to Liberia. This is according to new data from the Wellcome Global Monitor, a worldwide poll of more than 140,000 people in 144 countries.

France may be on the extreme end, but it’s part of a global trend that has many health experts worried.

Trust in vaccination programmes is crucial to maintaining high immunity rates. But across the EU, people are delaying or even refusing vaccines, contributing to a rise in disease outbreaks.

Between 2010 and 2017, over half a million French infants didn’t receive a first dose of the measles vaccine. And last year, France was among the ten countries with the highest year-on-year increases in measles, with confirmed cases jumping from just over 500 in 2017 to nearly 3,000 in 2018.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), reluctance or refusal to vaccinate is now one of the top ten major threats to global health. One manifestation of this is that even people in high-income countries, with good healthcare systems, are dying from easily preventable diseases. More than 70 people died of measles across Europe in 2018 – three of them in France.

‘It’s a tragedy for Europe that a child or an adult has died because of a preventable disease,’ says Patrick O’Connor, a team lead in WHO Europe’s Vaccine-Preventable Diseases and Immunization programme. ‘We owe it to them to protect them.’

A critical mass of unvaccinated people produces a wildfire effect, O’Connor adds. ‘Next year it could be diphtheria, or a variety of things.’

Read the full article in Mosaic.

Low-income African countries ‘pay 30 times more’ for drugs

BBC News, 18 June 2019

African countries with small to medium-sized economies pay far more money for less effective drugs, a leading health expert has told BBC Newsday.

In countries such as Zambia, Senegal and Tunisia, everyday drugs like paracetamol can cost up to 30 times more than in the UK and USA.

Drug markets in poorer countries ‘just don’t work’, said Kalipso Chalkidou from the Centre for Global Development.

She said ‘competition is broken’ due to a ‘concentrated supply chain’.

Ms Chalkidou, director of global health policy at the organisation, co-authored a report on drug procurement that concluded that small to middling economy countries buy a smaller range of medicines, leading to weaker competition, regulation and quality.

It says richer countries, thanks to public money and strong processes for buying drugs, are able to procure cheaper medicines.

Poorer countries, however, tend to buy the most expensive medicines, rather than cheaper unbranded pharmaceuticals which make up 85% of the market in the UK and US.

The very poorest countries are not affected when foreign donors purchase medicine on their behalf, meaning their over-the-counter medicines remain at low cost.

‘In the middle it’s very problematic,’ Ms Chalkidou said.

Low- to middle-income countries ‘have little ability to negotiate prices down and quality assure products’ and there are lots of mark-ups, often due to taxes and corruption.

Read the full article on BBC News.

Massacre and uprising in Sudan

Shireen Akram-Boshar & Brian Been, Jacobin, 13 June 2019

The massacre of June 3 came just days after the leaders of the Transitional Military Council, General Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman al Burhan and his deputy, General Hemedti, attended a series of meetings convened by the Saudis in Mecca with the Arab League and the Gulf Cooperation Council. Burhan and Hemedti have long-standing ties with Saudi Arabia through their participation in the Saudi-led war in Yemen that has plunged that country into a humanitarian crisis. The Saudi-UAE coalition has used Sudanese soldiers to outsource the war on Yemen, diminishing the number of Saudi lives lost and thus dampening internal dissent.

The tens of thousands of Sudanese soldiers sent to fight in Yemen have been reported to include numerous child soldiers from the Darfur region. Motivating the war on Yemen is Saudi Arabia’s ongoing imperial rivalry (with absolute support from US) with Iran for regional dominance. It should also be noted that this anti-Iran alignment has driven the Gulf countries into closer cooperation with Israel, one consequence of which is the upcoming Bahrain conference, where the Trump administration plans to unveil its so-called ‘deal of the century’ sell-out of the Palestinian people.

Competition with Iran, partly at the behest of the US, drives the active backing for the Transitional Military Council (TMC) by the regional forces of counterrevolution, and their efforts quell the aspirations of the Sudanese people. On Sunday, June 2, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates pledged to send three billion dollars in aid to Sudan. The Emirati crown prince, Mohammed bin Zayed, vowed to ‘preserve Sudan’s security and stability.’ Egyptian president — and counter-revolutionary extraordinaire — Sisi has used his position at the head of the African Union (AU) to support the TMC and block attempts by the AU to condemn it, although last Monday’s massacre finally drove the AU to suspend Sudan. The timing of the bloodbath undoubtedly was reviewed and green-lit by these regional powers.

While the US made statements condemning the excesses of the recent violence, this should in no way be equated with support for the uprising, as the distancing is only cosmetic. Saudi actions are carried out in lockstep with the strategy of the country’s US ally in its attempts to isolate Iran. Trump’s plans to bypass Congress to keep weapons flowing into Yemen represent just one small example of this.

Russia has taken a more belligerent stance, echoing the RSF’s earlier statements of justifying the massacre and stating that the violence of June 3 ‘need[ed] to be done for order to be imposed and fight against extremists’ — the same language Russia used to express their support for the butchery of Bashar al-Assad in Syria’s own revolution.

Read the full article in Jacobin.

A waste of 1,000 research papers

Ed Yong, The Atlantic, 17 May 2019

In 1996, a group of European researchers found that a certain gene, called SLC6A4, might influence a person’s risk of depression.

It was a blockbuster discovery at the time. The team found that a less active version of the gene was more common among 454 people who had mood disorders than in 570 who did not. In theory, anyone who had this particular gene variant could be at higher risk for depression, and that finding, they said, might help in diagnosing such disorders, assessing suicidal behavior, or even predicting a person’s response to antidepressants.

Back then, tools for sequencing DNA weren’t as cheap or powerful as they are today. When researchers wanted to work out which genes might affect a disease or trait, they made educated guesses, and picked likely ‘candidate genes.’ For depression, SLC6A4 seemed like a great candidate: It’s responsible for getting a chemical called serotonin into brain cells, and serotonin had already been linked to mood and depression. Over two decades, this one gene inspired at least 450 research papers.

But a new study – the biggest and most comprehensive of its kind yet—shows that this seemingly sturdy mountain of research is actually a house of cards, built on nonexistent foundations.

Richard Border of the University of Colorado at Boulder and his colleagues picked the 18 candidate genes that have been most commonly linked to depression – SLC6A4 chief among them. Using data from large groups of volunteers, ranging from 62,000 to 443,000 people, the team checked whether any versions of these genes were more common among people with depression. ‘We didn’t find a smidge of evidence,’ says Matthew Keller, who led the project.

Between them, these 18 genes have been the subject of more than 1,000 research papers, on depression alone. And for what? If the new study is right, these genes have nothing to do with depression. ‘This should be a real cautionary tale,’ Keller adds. ‘How on Earth could we have spent 20 years and hundreds of millions of dollars studying pure noise?’

Read the full article in the Atlantic.

Ireland’s unequal tech boom

Naomi O’Leary, Politico, 13 June 2019

If one person could embody the paradox of Ireland’s tech boom, John would come close.

By day, his job is to do whatever it takes to maintain the five-star ratings of Airbnb apartments in the Irish capital. He fixes appliances, cleans, and responds to guest complaints at a string of Airbnbs managed by an agency in Dublin’s city center.

By night, John sleeps in a vacant Dublin property as one of Ireland’s record 10,000 homeless people. His zero-hours contract means he does not know how long he’ll work each day — or how much he’ll get paid — with hours ranging between two and 13.

Ireland is in the throes of a severe housing crisis, with hundreds of families priced out of the private rental sector, often due to evictions, and forced into emergency accommodation in hotels or bed and breakfasts.

House prices, rents and homelessness have all hit record highs, even as tech giants and multinationals swell employment figures and GDP.

‘The tourists are in the apartments, and the Irish people are in the hotels,’ John, who insisted on a pseudonym and that his company not be named to protect his job, told Politico.

The crisis has been a long time in the making. A phalanx of international investment funds bought up Irish property and mortgages at fire-sale prices following the crash a decade ago. At the same time, Ireland’s building sector collapsed, many of its tradesmen emigrated, and lending for construction evaporated, causing population growth to outstrip house building.

Now, house prices have almost doubled since their 2012 low, and rents have been rising by double figures annually. As investors seek to cash in by raising rents or foreclosing on houses owned by people in mortgage arrears, so-called vulture funds have become public bogeymen and the target of protests.

Read the full article in Politico.

In court, Facebook blames users

for destroying their own right to privacy

Sam Biddle, The Intercept, 14 June 2019

But only months after Zuckerberg first outlined his ‘privacy-focused vision for social networking’ in a 3,000-word post on the social network he founded, his lawyers were explaining to a California judge that privacy on Facebook is nonexistent.

The courtroom debate, first reported by Law360, took place as Facebook tried to scuttle litigation from users upset that their personal data was shared without their knowledge with the consultancy Cambridge Analytica and later with advisers to Donald Trump’s campaign. The full transcript of the proceedings — which has been quoted from only briefly — reveal one of the most stunning examples of corporate doublespeak certainly in Facebook’s history.

Representing Facebook before U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria was Orin Snyder of Gibson Dunn & Crutcher, who claimed that the plaintiffs’ charges of privacy invasion were invalid because Facebook users have no expectation of privacy on Facebook. The simple act of using Facebook, Snyder claimed, negated any user’s expectation of privacy:

There is no privacy interest, because by sharing with a hundred friends on a social media platform, which is an affirmative social act to publish, to disclose, to share ostensibly private information with a hundred people, you have just, under centuries of common law, under the judgment of Congress, under the SCA, negated any reasonable expectation of privacy.

An outside party can’t violate what you yourself destroyed, Snyder seemed to suggest. Snyder was emphatic in his description of Facebook as a sort of privacy anti-matter, going so far as to claim that ‘the social act of broadcasting your private information to 100 people negates, as a matter of law, any reasonable expectation of privacy.’ You’d be hard-pressed to come up with a more elegant, concise description of Facebook than ‘the social act of broadcasting your private information’ to people. So not only is it Facebook’s legal position that you’re not entitled to any expectation of privacy, but it’s your fault that the expectation went poof the moment you started using the site (or at least once you connected with 100 Facebook ‘friends’)…

Again and again, Snyder blames the targets of surveillance capitalism for their own surveillance:

This is why every parent says to their child, ‘Do not post it on Facebook if you don’t want to read about it tomorrow morning in the school newspaper,’ or, as I tell my young associates if I were going to be giving them an orientation, ‘Do not put anything on social media that you don’t want to read in the Law Journal in the morning.’ There is no expectation of privacy when you go on a social media platform, the purpose of which, when you are set to friends, is to share and communicate things with a large group of people, a hundred people.

Read the full article in The Intercept.

Facebook’s new cryptocurrency Libra:

Not to be confused with libre

Privacy International, 19 June 2019

One of the key statements made about the currency and referenced repeatedly within the white paper is around decentralisation. Decentralisation lies at the heart of the ethos behind cryptocurrrencies: it is supposed to mean that no central banks, no state actors, and no centralised management can control the currency. Libra on the other hand is the polar opposite. The Libra Association, which oversees the development of the currency may be a not-for-profit, but the founding partners are overwhelmingly US-based companies, including Facebook, Mastercard, and PayPal. Together these and other companies amount to more than 70% of the ownership within the US.

If you consider these companies to be the equivalent to role played by central banks in traditional currencies, replacing them with companies accountable only to their shareholders is not real decentralisation. The Association claims it will move away from this flawed model of ‘decentralisation’ in the next five years – a claim which is impossible to verify…

An initial Customer Commitment of Calibra, a digital custodial wallet that enables storage and usage of the Libra digital currency, outlines some of the envisioned data sharing relationship between Facebook and the new payment service. Aside from limited cases, which are currently non-exhaustive, Calibra claims it will not share account information or financial data with Facebook, Inc. or any third party without customer consent. The key question for users is how Facebook will decide to implement consent and whether users will have a real choice, given Facebook’s dominance as a company and platform.

The envisaged data flows from Facebook to Calibra, however, are much more open: ‘Calibra will use customer data to facilitate and improve the Calibra product experience, market Calibra products and services, comply with legal and regulatory obligations, and ensure safety, security, and integrity. We may also use customer data to conduct research projects related to financial inclusion and economic opportunity with, for example, academic institutions and NGOs, though any published results will only contain aggregated statistics.’ This suggests that Facebook might offer credit or insurance products that rely on Facebook data. PI has documented the inevitable challenges that come with such alternative forms of credit scoring in our report on financial technology, and how insurance companies such as Admiral have tried to take advantage of such data for personality profiling.

Advertising is the core business model of Facebook. Financial data opens new avenues for many of the companies involved as it allows the direct provision of products and services, be that lines of credit or insurance, or tangible things like taxis or telecommunications. This won’t unfortunately usher in a utopian world of open access to services. Instead, it will be based on even more intimate profiling of individuals allowing organisations to offer products and services with discriminatory pricing based on a large dossier of data.

Read the full article on Privacy International.

How a small Turkish city

successfully absorbed half a million migrants

Stephen Burgen, Guardian, 19 June 2019

Imagine you live in a medium-sized city such as Birmingham or Milan. Now imagine that overnight the population increases by about 30%. The new people are mostly destitute, hungry and with nowhere to stay. They don’t even speak the language.

Then imagine that instead of driving them away, you make them welcome and accommodate them as best you can.

Welcome to Gaziantep, a sprawling industrial city on Turkey’s southern border with Syria, where that exact scenario has played out over the past few years.

Gaziantep has a thriving textile industry and is the home of the pistachio; its food is reputed to be so good that people fly down from Istanbul just for lunch. It is also just 60 miles from Aleppo, the Syrian city devastated by war.

In April 2011, 252 refugees arrived in Turkey from the Aleppo area. One year later, there were 23,000 in the country; by 2015, 2 million. Today there are 3.6 million Syrian refugees (or protected persons, as they are officially known) in Turkey, with the majority living in the south, in places such as Gaziantep.

In one 24-hour period alone, Gaziantep took in 200,000 people. To put that in perspective, Turkey’s biggest city, Istanbul, with a population of 15 million, hosts 560,000 refugees in total. Gaziantep has just a 10th of the population but took in 500,000.

Early on, the Turkish government pursued a policy of integrating the newcomers into urban areas, rather than let them fester in refugee camps. Only 4% still live in camps.

This put pressure, however, on the existing housing stock in Gaziantep, forcing up rents. Employers, meanwhile, took advantage of the sudden increase in the workforce to push down wages. There was also conflict over access to drinking water, and burgeoning resentment that the aid pouring in was going to Syrians, not to poor Turks.

‘If you go into a neighbourhood in a UN vehicle, everyone knows who is getting the aid and this can potentially cause tension,’ says Khalil Omarshah of the Gaziantep branch of the International Office for Migration (IOM), the main world body tasked with moving refugees approved for resettlement to third countries.

It was precisely to avoid this sort of conflict that the city adopted a new approach, based on integration.

The mayor, Fatma Sahin, established a migration management department. The idea was that Turks and migrants would receive equal treatment and benefits.

Read the full article in the Guardian.

In Iraq Museum, there are things

‘that are nowhere else in the world’

Alissa J Rubin, New York Times, 9 June 2019

If people remember anything about the Iraq Museum, it is most likely the televised images of it being looted in 2003 as American troops watched from their tanks.

Statues too heavy to move were knocked from their pedestals, their 3,000- and 4,000-year-old shoulders bashed to powder. Some lost their eyes or one side of their face. Glass cases were shattered, their contents gone or thrown on the floor.

One of the museum’s most treasured art works was the Warka vase, with carvings dating back five millenniums showing that even then the ancient Mesopotamians grew wheat and fruits, wove cloth, and made pottery. When someone walked off with it, a bit of human history was lost.

The same was true of the Golden Lyre of Ur, a 4,500-year-old musical instrument inlaid with gold, silver and carnelian.

I was there in 2003 on the second morning of looting and was stopped about 150 feet from the museum entrance by crowds of Iraqis rushing by clutching clay objects I could not identify. They also carried more prosaic items — file cabinets, chairs and spools of electrical wire.

This spring, 16 years later, I was back at the museum. It had reopened in 2015 after conservationists had repaired some of the damage and European countries, among others, had helped restore several galleries. Still, I expected to see bare rooms and empty niches.

Instead, I found that despite the loss of 15,000 works of art, the museum was filled with an extraordinary collection…

The museum’s collection is so comprehensive that art historians say it is daunting to try to talk about it in its entirety.

‘What is so striking about the Iraq Museum is the chronological span that it covers,’ said Paolo Brusasco, an archaeologist and art historian at the University of Genoa, who has worked extensively in northern Iraq.

‘From the Assyrian period all the way to the Ottoman,’ he said.

Read the full article in the New York Times.

The trust gap: a challenge for science,

a challenge for society

Mark Henderson, LinkedIn, 20 June 2019

It’s what you might call the trust gap – the substantial differences in trust in science, and confidence that it works in your own interests, between those who are more and less educated and more and less comfortably off.

The figures are quite stark. Both within and between countries.

In high-income countries, people who say they are ‘finding it difficult’ are three times more likely than those who say they are ‘living comfortably’ to say that science benefits either them personally, or society as a whole. People with better access to communications – news, mobile phones, the internet – have stronger trust as well.

The level of overall trust that people have in scientists is also strongly correlated with a country’s Gini coefficient – the standard measure of inequality. In countries that are more unequal, people distrust science more. In countries that are more equal, trust is much higher.

By the same token, trust in science does not seem to develop in isolation. It’s strongly correlated with trust in other institutions, such as governments.

We’ve seen this before. The ‘trust gap’ between a well-informed, well-educated, economically comfortable minority, and a broader population that is not so privileged, isn’t unique to the Wellcome Global Monitor. This is a picture that’s already quite familiar, from the last few years of the Edelman Trust Barometer.

The annual Edelman survey suggests strongly that what’s true for trust in science is true much more broadly across society. For some years now, it’s found a consistent and widening gap between the extent to which an elite ‘informed public’ who follow the news and are well-educated and well-off, and the broader population, trust institutions of all kinds.

This year, Edelman found an 11 point gap in trust between the informed public (63%) and the general public (52%) worldwide, which was consistent to a greater or lesser extent across most geographies and pretty much all types of institution. This echoes a WGM finding that trust in science is fairly well correlated with trust in your national government and other institutions such as the military.

Trust in science, it seems, is quite likely to be a subset of a much broader question of trust in society.

Read the full article on LinkedIn.

How the poor are kept in their place

James Kirkup, UnHerd, 17 June 2019

Among the vast, awful canon of positive-thinking, self-help slogans and truisms, there is a quote attributed to Ella Fitzgerald: ‘It isn’t where you came from, it’s where you’re going that counts.’

That sounds nice, but it’s not really true, especially in Britain. Where you come from has a huge influence over where you end up, physically and economically. Grow up poor in the wrong place and you’re not just more likely to live poor and die poor – you’ll die sooner too. People in the poorest places die a decade or more before people in rich places.

The unusually big and largely unjustifiable differences between places in the UK should be a much bigger part of the debate about inequality. Geography matters as least as much as economics, and matters an awful lot more than a lot of people in politics have acknowledged during the last couple of decades.

Indeed, I suspect that if more people in the Westminster village (I am one of them) had paid a bit more attention to economic geography and the people who study it, we’d have been a bit less surprised by the events of the last few years.

Let’s start at the beginning, with education. Where you grow up matters a lot to whether you acquire the basic skills needed to do anything but the worst-paid, least stable work.

A couple of years ago, the Social Market Foundation pointed out that there are significant differences between 16-year-olds across England. In 2016, over 60% of pupils in London achieved five good GCSEs including English and Maths. In the West and East Midlands, the figure was just 55%.

Those differences carry out through the education system. In 2017, almost 42% of 18-year-olds in London accepted a university place. In the south-west, the figure was less than 29% and Scotland managed only 26%.

This pattern produces some extreme, eye-catching examples. I’m generally not a fan of using Oxbridge entry as a proxy for social mobility but sometimes the numbers speak volumes. In 2016, the number of children from the lowest-income homes from the north-east of England, Yorkshire and the Humber who got into Oxford or Cambridge was one. Yes, one…

Measured in terms of everyday lives, these differences are striking. Average household incomes today in the Midlands, the north and Wales are roughly equivalent to household income in the South East during the 1990s. Large parts of the country are economically decades behind the richest places.

Read the full article in UnHerd.

The first murder case to use

family tree forensics goes to trial

Megan Molteni, Wired, 10 June 2019

Jay Cook’s battered, barely 21-year-old body was discovered on Thanksgiving Day in 1987, two days after his 17-year-old girlfriend Tanya Van Cuylenborg was found dead in a ditch one county over. She had been shot in the head and was believed to have been sexually assaulted. The young Canadian couple had been reported missing for nearly a week, after they failed to return to their home on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, from an overnight errand to buy furnace parts in Seattle. Despite investigating hundreds of leads and subjecting crime scene samples to new DNA technologies as they arrived in the ’90s and 2000s, police never arrested any suspects. For more than three decades the case went unsolved.

Then in May of last year, Washington officials announced a breakthrough. Snohomish County Sheriff’s Detective Jim Scharf stood at a podium and told the reporters assembled that they had, at long last, arrested a suspect: a balding, middle-aged man who had grown up in the area named William Earl Talbott II. ‘He was never on any list law enforcement had, there was never a tip providing his name,’ said Scharf. ‘If it hadn’t been for genetic genealogy, we wouldn’t be standing here today.’

At the time, the statement probably didn’t mean much to most people beyond the Cook and Van Cuylenborg families. Talbott, who would later plead not guilty, was only the second person to be fingered using a new forensic technique known as genetic genealogy. It involves creating DNA profiles like the kind you’d get through 23andMe or Ancestry from crime scene samples and looking through public genealogy websites for matches, which could surface family members that lead to new suspects. The first, a California man accused of being the notorious Golden State Killer, had been taken into police custody mere weeks before.

Since then, the technique has been used to help identify suspects in at least 50 cases, even as critics warn it could mean the end of genetic privacy. Police departments and the Federal Bureau of Investigation have formed their own dedicated family tree-building units; multiple companies have launched lucrative genetic genealogy services, and it’s all happening with no federal or state laws to rein it in. Now the Talbott case, which begins this week, will be the first to put genetic genealogy on trial.

At stake is more than justice for Cook and Van Cuylenborg. The trial’s outcome could result in legal precedents that could determine the future of one of the most powerful and invasive tools for finding people to ever fall into the hands of law enforcement.

Read the full article in Wired.

Want to see my genes? Get a warrant

Elizabeth Joh, New York Times, 11 June 2019

We should be glad whenever a cold case involving a serious crimes like rape or murder can be solved. But the use of genetic genealogy in the Centerville assault case raises with new urgency fundamental questions about this technique.

First, there is now no downward limit on what crimes the police might investigate through genetic genealogy. If the police felt free to use it in an assault case, why not shoplifting, trespassing or littering?

Second, there’s the issue of meaningful consent. You may decide that the police should use your DNA profile without qualification and may even post your information online with that purpose in mind. But your DNA is also shared in part with your relatives. When you consent to genetic sleuthing, you are also exposing your siblings, parents, cousins, relatives you’ve never met and even future generations of your family. Legitimate consent to the government’s use of an entire family tree should involve more than just a single person clicking ‘yes’ to a website’s terms and conditions.

Third, there’s the question of why the limits on Americans’ genetic privacy are being fashioned by private entities. The Centerville police used GEDmatch because the site owners allowed an exception to their own rules, which had permitted law enforcement access only for murder and sexual assault investigations. After user complaints, GEDmatch expanded the list of crimes that the police may investigate on its site to include assault. It also changed default options for users so that the police may not gain access to their profiles unless users affirmatively opt-in. But if your relative elects to do so, there’s no way for you to opt out of that particular decision. And what’s to stop GEDmatch from changing its policies again?

Finally, the police usually confirm leads by collecting discarded DNA samples from a suspect. How comfortable should we be that a school resource officer hung around a high school cafeteria waiting to collect a teenager’s ‘abandoned’ DNA?

Read the full article in the New York Times.

Windrush: Archived documents show the long betrayal

David Olusoga, Observer, 16 June 2019

The big historical truth that we have yet to confront is wrapped up with the same painful truth that explains how the Windrush scandal of 2018 could have happened – that the arrival of the Empire Windrush in 1948 was unplanned and unexpected. The people on board were unwanted and their moment of arrival set in train two oppositional processes.

It established 1948 as the symbolic beginning of the postwar migration that created modern, multiracial Britain. At the same time it provoked a political struggle that saw successive British governments, both Labour and Conservative, set out to design and introduce laws to limit what they called ‘coloured migration’.

The great dilemma they faced was that any act that put limits on migration of British subjects from all parts of the empire would inevitably limit the movement of white people from the ‘white dominions’. Whereas draft legislation that overtly targeted the black and brown people would damage Britain’s standing in the world and undermine the creation of the Commonwealth – the rebranded, reimagined version of the empire that included newly independent states, as well as the old dominions. In an interview in 1954, Winston Churchill’s private secretary Sir David Hunt explained the dilemma: ‘The minute we said we’ve got to keep these black chaps out, the whole Commonwealth lark would have blown up.’

The political struggles of the period that followed the arrival of the Windrush are recorded on the pages of hundreds of documents held at the National Archives. What they reveal is that even before the Windrush set sail from Kingston, British politicians had concluded that ‘coloured migration’ automatically represented a ‘colour problem’ and was thus to be discouraged and curtailed. The other deeper and more fundamental and unquestioned belief that runs through those thousands of archival pages is that black and brown people could never really be British.

Read the full article in the Observer.

Can placebo surgery ever be ethical?

David Papineau, New Statesman, 10 June 2019

I had a chance to find out more about the thinking behind the CSAW project when the lead author of the study, Professor David Beard, gave a talk at King’s College London a couple of years ago about the work of the Oxford Surgical Intervention Trials Unit, of which he is co-director. When pressed about the limited information given to the patients enrolled in the CSAW study, he allowed that some ‘sleight of hand’ had been involved, but pointed to the many future operations that would be avoided. He said that the researchers viewed it as a utilitarian calculation, with the boon of greater medical knowledge justifying leaving patients somewhat in the dark. As he saw it, if patients couldn’t be induced to enrol in surgical studies, we would never escape from the dark ages of medical ignorance.

The contemporary commitment to ‘evidence-based medicine’ has led to enormous resources being devoted to the rigorous assessment of all aspects of medical practice. Even so, patient deception is generally regarded as a red line that violates the trust that patients place in their doctors. One senior academic doctor of my acquaintance, second to none in his enthusiasm for medical trials, described the CSAW study to me as ‘brave’. He admired its ambition – but even he felt that it pushed the envelope of ethical constraints on medical research.

The CSAW study is only one case, but it illustrates a danger that is inherent in all randomised controlled trials. Trials of this kind, in which patients are assigned to different ‘treatment groups’ at random, are regarded as an essential investigative tool by medical researchers. They don’t trust ordinary ‘pilot’ studies that lack any comparison group or retrospective surveys that simply chart past treatment success. As they see it, randomisation is the only way that to be sure that observed positive outcomes are really due to the relevant treatment itself, and not the result of some extraneous influence.

But by their nature, randomised trials need selling to patients. The different treatments involved in a trial will not generally offer them the same expected benefits. This is most obvious with placebo treatments that lack any active medical ingredient. But even among non-placebo treatments, initial evidence will often favour one over the others. In any such set-up, it will be tempting for doctors to be less than fully open with their patients. After all, once prospective trial subjects understand that they could end up with an inferior treatment as a result of a coin-toss, they might understandably be disinclined to take part.

Read the full article in the New Statesman.

Placebo surgery raises ethical concerns –

but this was not placebo surgery

Andy Carr, David Beard & Julian Savulescu,

New Statesman, 10 June 2019

David Papineau raises some important points about deception and therapeutic misconception in medical research, but this is the wrong trial to pick on to make that point. Three of the authors of the ethics article in the Journal of Medical Ethics which he approvingly cites were also investigators in CSAW. We are well aware of the importance of an honest, transparent and intelligible consent process. It is because of concern with the ethics of such a trial that one of our number, Andrew Carr, invited Julian Savulescu – a professor of practical ethics and expert in medical ethics – to be involved at the stage of trial design.

The first point he brought up was that there must be no deception. They together wrote an article with another investigator to explore more deeply how surgical placebo controlled trials should be conducted ethically and believe this trial conformed to those standards. This built on a widely cited systematic review of the results of all surgical placebo controlled trials published in the BMJ led by the same authors. It is hard to imagine a more rigorous process of ensuring a trial is designed and conducted ethically.

The term placebo can be defined in various ways: we chose, after careful consideration, to define it for the purposes of trial design and description as ‘surgery with the critical therapeutic element omitted’, in this case the removal of the bone spur. The established rationale for the operation is that a spur of bone is causing pain due to mechanical contact with tendons and soft tissue during movement and that removal of the spur will cure the problem.

The patients were very carefully and clearly made aware in the consenting process that if randomised to surgery they had a 50 per cent chance of having the spur removed and a 50 per cent chance of it being left untouched with no tissue removed. The trial design, consent process and patient information leaflet were considered and approved by an independent NHS Health Research Authority Research and Ethics Committee. These committees, which include patients and lay members as well as clinical trial experts, have the dual mission, firstly, to ensure the protection of the rights, dignity and wellbeing of research participants and, secondly, to promote ethical research that is of potential benefit to participants, science and society.

Read the full article in the New Statesman.

Facial recognition smart glasses could make

public surveillance discreet and ubiquitous

James Vincent, The Verge, 10 June 2019

From train stations and concert halls to sport stadiums and airports, facial recognition is slowly becoming the norm in public spaces. But new hardware formats like these facial recognition-enabled smart glasses could make the technology truly ubiquitous, able to be deployed by law enforcement and private security any time and any place.

The glasses themselves are made by American company Vuzix, while Dubai-based firm NNTC is providing the facial recognition algorithms and packaging the final product.

The technology has been dubbed iFalcon Face Control Mobile by NNTC and goes on sale in May, with pricing on a per-project basis.

The AR glasses have an 8-megapixel camera embedded in the frame which allows the wearer to scan faces in a crowd and compare with a database of 1 million images. Notifications about positive matches are sent to the glasses’ see-through display, embedded in the lens.

NNTC boasts that its facial recognition algorithms are in the top three for accuracy in the US government’s Face Recognition Vendor Test, able to detect up to 15 faces per frame per second, and capable of identifying an individual in less than a second. That being said, the performance of these algorithms always varies in the wild, and the fake video demo below definitely shouldn’t be seen as a reflection of real-world performance.

NNTC says it’s so far produced 50 pairs of facial recognition-enabled glasses, and that they are ‘currently being deployed into several security operations’ in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates. The company says the glasses are only on sale to security and law enforcement.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen facial recognition embedded in glasses. Police forces in China deployed similar tech last year, using the hardware at train stations to pick out suspects in a crowd. The technology was also used to keep blacklisted individuals like journalists, political dissidents, and human rights activists away from the annual gathering of China’s National People’s Congress, a pseudo-parliament with 3,000 delegates.

Although technology like this seems particularly futuristic or dystopian, it’s not functionally too dissimilar from what is already deployed in the US and other Western countries. Police in America can use imagery collected from body cameras and CCTV cameras to search for suspects using facial recognition software, while in the UK facial recognition cameras are deployed at events like soccer matches using specially equipped vans.

Read the full article in The Verge.

Two giant Buddhas survived 1500 years.

Fragments, graffiti and a hologram remain.

Rod Norland, New York Times, 18 June 2019

When the Taliban demolished the Buddhas, in an important sense they botched the job.

The Buddhas, built over perhaps a century from 550 A.D. or so, were just the most prominent parts of a complex of hundreds of caves, monasteries and shrines, many of them colorfully decorated by the thousands of monks who meditated and prayed in them.

Even without the Buddhas themselves, their niches remain, impressive in their own right; the Statue of Liberty would fit comfortably in the western one.

Unesco has declared the whole valley, including the more than half-mile-long cliff and its monasteries, a World Heritage Site.

‘If the Taliban come back again to destroy it, this time they would have to do the whole cliff,’ Aslam Alawi, the local head of the Afghan culture ministry, said.

Unesco has also declared the Bamiyan Buddhas complex a ‘World Heritage Site in Danger,’ one of 54 worldwide. The larger western niche is still at risk of collapsing.

Most archaeologists oppose restoration, arguing that the damage was too great and that the cost would be prohibitive. Estimates range from $30 million for one Buddha to $1.2 billion for the whole complex.

Others argue that the destruction itself has become a historical monument, and that the ruins should be preserved as is, a visible reminder of Taliban iconoclasm.

A scientific conference in Tokyo in 2017 — involving Afghans, Unesco, scientists and donors — met to study the matter, and to discuss Afghanistan’s formal request for money to rebuild the eastern Buddha. A diplomatically worded final statement called for more study and an indefinite pause in restoration work.

Or, as the Unesco field officer Ghulam Reza Mohammadi in Bamiyan put it, ‘The Buddhas will never be rebuilt.’

The important thing is stabilization and conservation of the remains as they are, Mr. Mohammadi said.

‘The government can’t even afford to pay for five guards they promised,’ he said.

Read the full article in the New York Times.

Exhibiting change: When some of the best-attended exhibitions in museums are protests, where do institutions go from here?

Barbara Pollack, Artnews, 5 May 2019

Once ivory towers of culture, far removed from politics and controversy, museums have increasingly come into the spotlight as sites of protest and places where equity, diversity, and inclusion have become imperatives. From the push of the New Museum’s staff for unionization to the Museum of Modern Art’s plans to reinstall its permanent collection to reflect a diversified canon, museums across the country are now more than ever under pressure to change, both for practical and ethical reasons. Museum directors, ever aware of the need to address changing demographics and the demands of social media–savvy audiences, are adapting to this evolution, though for many, this is a sharp departure from their traditional training in art history and curatorial studies…

You could say that the times of museum unrest began in 2017, with the controversy over Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, Open Casket (2016), whose showing at the Whitney Biennial that year was met with now-famous demands that the exhibition’s curators remove and destroy it, due to the image’s capitalizing on the pain of black Americans. (The work by Schutz, who is white, remained intact and on view for the show’s full run.) Or you could say it began before that, at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, where a fall 2016 exhibition of paintings by Georgia-born artist Kelley Walker triggered a public boycott. Walker, who is white, employed appropriated images of African-Americans, and smeared them with chocolate and toothpaste, angering a group of protesters who called for the exhibition to be removed. The museum responded with a town hall discussion and shortly thereafter, the show’s curator left the institution.

‘I really believe that a museum becoming a site of protest is something that in some ways should happen,’ CAM’s director, Lisa Melandri, said recently. For her, increased sensitivity on the part of museums is a positive development. ‘That moment of protest is a place where you gain an acute awareness that something is affecting people seriously deeply and . . . protest is the way they manifest that criticism. It’s a moment for us inside the institution to gain that awareness and to listen.’ As a result of the controversy, practices at CAM have changed. The full staff, including education and public relations, are brought in early in the discussions about potential shows at the museum, as is the board. Melandri says that this is not a new policy so much as a change in practice, doing what they have already done but with increased sensitivity. ‘We are really digging into by whom and for whom is the art. We’re much more involved in longer conversations about how the work will function in the public sphere and to whom will it give voice. The process can sometimes be painful but I don’t think that makes it bad.’

Read the full article in Artnews.

Retreat of the scholars

Richard A Greenwald, The Baffler, 17 June 2019

Fitzpatrick’s book is based on a singular premise: the need to rebuild ‘a relationship of trust between universities and the publics they are meant to serve.’ When she looks around at the landscape of higher education she sees that some of the public’s current distrust was brought on by ourselves, as we have built a system that is ‘seen as privileging the negation rather than the creation of ideas and institutions.’ As institutions, we inhabit a culture of advanced critique, of negativity. We have allowed our spaces to become acute places of competition. Therefore, academics tend to see our roles as gladiators, cutting down others. And, according to Fitzpatrick we teach this form of intellectual contact sport to our graduate and undergraduate students. We have taught ourselves to pounce, to evade, and to reject in an effort to get our own, better ideas out there. We have embraced narrow jargon to demonstrate mastery of field. In the process, we have lost the most important intellectual skill of all: the ability to sit patiently listening and understanding. And herein lies Fitzpatrick’s main argument: ‘the best of what the university has to offer lies less in its specific power to advance knowledge or solve problems in any of its many fields than in its more general, more crucial ability to be a model and a support for generous thinking as a way of being in and with the world.’ We have turned inward exactly when we needed to turn outward.

Fitzpatrick asks the key question: ‘How might we begin to rebuild strong and flourishing ties between the university and the public good?’ She reminds us that for much of the history of the United States higher education was seen as a social good. But, recently it has ‘come to be described as providing primarily private, individual benefits.’ She goes on to argue that we need ‘to turn away from efficiency as a primary value . . . [to a new system that values] building of relationships and the cultivation of care.’ She argues that our obsession with seeing higher education only through a job training lens means that anything ‘that does not lead directly to economic growth [was] . . . a misappropriation of resources.’ It is as if we have given up on the idea of the academy, a community that extends beyond individual institutions. Instead, we are now left with only the university, a set of institutions that exist in a hyper-competitive world. This competition rests on an understanding of prestige, a landscape that limits our ability to connect beyond our disciples and institutions. In this system, we value the individual over the social, losing our authority in the process.

Read the full article in The Baffler.

The unacknowledged legislators of the online world

The Economist, 15 June 2019

They are paid to spend their days watching filth: beheadings and chemical-weapons attacks, racist insults and neo-Nazi cartoons, teenagers encouraging each other to starve, people having sex with animals or with ex-lovers against whom they want revenge. When batches of images leap onto their screens, they must instantly sort them into categories, such as violence, hate speech and ‘dare’ videos, in which people offer to do whatever a stranger asks. If the material violates the platform’s explicit policies (nudity, sensationalistic gore), they take it down. If it contains suicide threats or evidence of a crime, they alert law-enforcement authorities. If it is a borderline case (violence with possible journalistic content, say), they mark it for review. Some earn $15 an hour, some a piece-work rate of a few cents per item, sorting anywhere from 400 to 2,000 a day.

With soldierly bravado, they insist the job does not upset them. ‘I handle stress pretty well,’ says one of the social-media content moderators interviewed by Sarah Roberts in ‘Behind the Screen’—before admitting to gaining weight and developing a drink problem. They avoid discussing their work with friends or family, but it intrudes anyway. War-zone footage, child sex-abuse and threats of self-harm are especially hard to repress. ‘My girlfriend and I were fooling around on the couch or something and she made a joke about a horse,’ says another moderator. ‘And I’d seen horse porn earlier in the day and I just shut down.’

Those who work directly for the big American internet platforms may boast about it to their friends, but they are mainly on short-term contracts with little kudos or chance of promotion. At a huge Silicon Valley firm that Ms Roberts calls MegaTech, the content moderators were barred from using the climbing wall. Even further down the hierarchy are third-party contractors in India and the Philippines, who handle material for corporate websites, dating sites and online retailers, as well as for the big platforms. Whether in San Francisco or Manila, their task is fundamentally the same. These are the rubbish-pickers of the internet; to most of the world, they are all but invisible.

Read the full article in the Economist.

Civic honesty around the globe

Alain Cohn, Michel André Maréchal,

David Tannenbaum & Christian Lukas Zünd,

Science, 20 June 2019

Our wallets were transparent business card cases, which we used to ensure that recipients could visually inspect without having to physically open the wallet (fig. S1). Our key independent variable was whether the wallet contained money, which we randomly varied to hold either no money or US $13.45 (‘NoMoney’ and ‘Money’ conditions, respectively). We used local currencies, and to ensure comparability across countries, we adjusted the amount according to each country’s purchasing power. Each wallet also contained three identical business cards, a grocery list, and a key. The business cards displayed the owner’s name and email address, and we used fictitious but commonplace male names for each country. Both the grocery list and business cards were written in the country’s local language to signal that the owner was a local resident.

After walking into the building, one of our research assistants (from a pool of eleven male and two female assistants) approached an employee at the counter and said, ‘Hi, I found this [pointing to the wallet] on the street around the corner.’ The wallet was then placed on the counter and pushed over to the employee. ‘Somebody must have lost it. I’m in a hurry and have to go. Can you please take care of it?’ The research assistant then left the building without leaving contact details or asking for a receipt. Our key outcome measure was whether recipients contacted the owner to return the wallet. We created unique email addresses for every wallet and recorded emails that were sent within 100 days of the initial drop-off. Complete methods and results, including additional robustness checks such as testing for experimenter effects, can be found in the supplementary materials.

As shown in the left half of, our cross-country experiments return a remarkably consistent result: citizens were overwhelmingly more likely to report lost wallets with money than without. We observed this pattern for 38 out of our 40 countries, and in no country did we find a statistically significant decrease in reporting rates when the wallet contained money. On average, adding money to the wallet increased the likelihood of reporting a wallet from 40% in the NoMoney condition to 51% in the Money condition (P < 0.0001). This result holds when controlling for a number of recipient and situational characteristics (table S8). Furthermore, while rates of civic honesty vary substantially from country to country, the absolute increase in honesty across conditions was stable. The average treatment effect is roughly equal in size across quartiles based on absolute response rates.

Citizens displayed greater civic honesty when the wallets contained money, but perhaps this is because the amount was not large enough to be financially meaningful. To examine this possibility we also ran a ‘BigMoney’ condition in three countries (US, UK, and Poland) that increased the money inside the wallet to US $94.15, or seven times the amount in our original Money condition. Reporting rates in all three countries increase even further when the wallets contained a sizable amount of money. Pooled across the three countries, response rates increased from 46% in the NoMoney condition to 61% in the Money condition, and topped out at 72% in the BigMoney condition (P < 0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons).

Read the full article in Science.

Surrogate pregnancy battle pits

progressives against feminists

Vivian Wang, New York Times, 12 June 2019

The proposal to legalize surrogacy in New York was presented as an unequivocal progressive ideal, a remedy to a ban that burdens gay and infertile couples and stigmatizes women who cannot have children on their own.

And yet, as the State Legislature hurtles toward the end of its first Democrat-led session in nearly a decade, the bill’s success is anything but certain.

Long-serving female lawmakers have spoken out against it. Prominent feminists, including Gloria Steinem, have denounced it. Women’s rights scholars have argued that paid surrogacy turns women’s bodies into commodities and is coercive to poor women given the sizable payments it can bring.

With just one week remaining in this year’s legislative session, what supporters have presented as an obvious move — 47 other states permit surrogacy — has turned into an emotional debate about women’s and gay rights, bodily autonomy and New York’s reputation as a progressive leader…

The debate over surrogacy rights is relatively new, as it is inherently entwined with advances in reproductive technology. Its roots are in the infamous Baby M case, when Mary Beth Whitehead, a woman in New Jersey, answered a newspaper ad in 1984 to be a surrogate for another couple, Elizabeth and William Stern.

But after Ms. Whitehead gave birth to a girl, known in court papers as Baby M, she changed her mind: She wanted to keep the baby, who was biologically her daughter, as she had used her own egg for the pregnancy. A protracted legal battle ensued, and the New Jersey Supreme Court eventually ruled that surrogacy contracts went against public policy. The Sterns won custody of the baby.

In the wake of that case, some states, including New York, banned surrogacy. But that trend has reversed in recent years. Washington State and New Jersey legalized paid surrogacy last year, joining about a dozen other states. Many other states allow it under certain circumstances or have no laws on the topic, effectively permitting it.

Between 1999 and 2014 in the United States, more than 18,400 infants were born through gestational surrogacy, where the carrier is not related to the fetus. Of those, 10,000 were born after 2010, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Yet the opposite has happened internationally. Surrogacy is illegal in most of Europe. And India — where so-called fertility tourism brought in $400 million each year — outlawed commercial surrogacy last year, over worries about exploitation.

Read the full article in the New York Times.

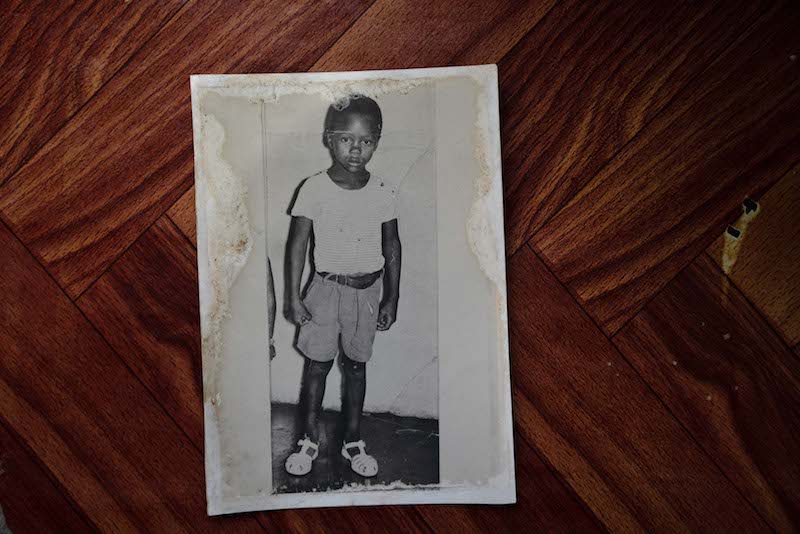

The forgotten massacre of 18 June 1976

Dennis Webster, New Frame, 14 June 2019

When the world remembers the 16th of June 1976, Emily Mavimbela remembers the 18th. There was no cup of tea waiting for her at home after work. On any other day, the elder of her two sons, Sipho, would have poured her a cup. It was her favourite. Sipho would also have cleaned the kitchen by then. He was studiously tidy.

But Sipho, 17, never came home from school.

Mavimbela went in search of her son. For three days, she traced a futile circuit of clinics and hospitals. Eventually, on 21 June 1976, she found his body lying naked on the floor of Johannesburg’s state mortuary. The bullets that had been fired into Sipho’s chest had torn his back open when they left his body. Mavimbela buried him in the Alexandra cemetery five days later.

While a magistrate later confirmed to Mavimbela that the bullets had been fired by a police officer, official records maintain that Sipho was ‘presumably’ killed by the police, and that liability for his death ‘cannot be determined’.

Sipho was one among at least 34 people mowed down by the police in Alex, north of Johannesburg, on 18 June 1976. Now 80, her hands made soft and arthritic by a lifetime of washing by hand as a domestic worker, Mavimbela is among those who lost loved ones in the now almost forgotten massacre.

The student uprisings that shook apartheid’s foundations had begun in Soweto two days earlier. They soon spread. By 18 June 1976, powder kegs filled over generations of white minority rule on Gauteng’s East Rand and on campuses at the universities of Zululand and the North – two institutions designated for black Africans during apartheid – had been lit.

Alex, however, was the first and bloodiest stop in Soweto’s widening gyre.

Read the full article in New Frame.

Ghosts in the network

Rachel Connolly, LRB Blog, 7 June 2019

Researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute have published a study projecting ‘the future accumulation of profiles belonging to deceased Facebook users’. Carl Öhman and David Watson used the social network’s ‘audience insights’ data, which businesses use to target their adverts, to find out how many ‘monthly active users’ of different ages there are across the world, and combined this with life expectancy data to create their models. If Facebook continues to grow at its current rate, by 2100 it will host the accounts of 4.9 billion dead people.

That’s an upper limit; the lower limit – if Facebook acquires no new users between now and the end of the century – is 1.4 billion, ‘fully 98 per cent of the 1.43 billion users in our dataset’. The researchers concede that ‘both scenarios are implausible’ – the actual figure will be somewhere between the two extremes – but they show that ‘Facebook will indubitably have hundreds of millions of dead users by 2060 if not sooner.’

Nobody knows how many dead users Facebook has now; probably not even Facebook. It won’t publish official figures (despite being constantly embroiled in privacy scandals, it’s very guarded about the data it releases). When someone dies, their friends or family can report it and have the account ‘memorialised’. You can appoint someone as a ‘legacy contact’ to manage your account after your death, or you can choose to have your account deleted by going to your ‘memorialisation settings’ and selecting ‘delete after death’. Many accounts, however, are neither deleted nor memorialised, but left more or less as they were: ghosts in the network.

Facebook’s algorithms blithely carry on including the dead in ‘highlights of the year’ videos, and suggesting them as invitees for parties. In April, Sheryl Sandberg announced that the company is actively working to get ‘faster and better’ at detecting dead accounts to stop this happening, but admitted it was not straightforward…

It isn’t only users’ life-or-death status that Facebook can misrepresent. On a micro level, almost nothing on my Facebook page is a true reflection of my life: some events and relationships are over documented, and everything else is ignored. On a macro level, Facebook boasted to advertisers in 2017 that it had 41 million users aged between 18 and 24 in the United States; according to the US census, there were only 31 million people in that age group.

Read the full article on the LRB Blog.

Transwomen and adoptive parents: An analogy

Sophie Grace Chappell,

Conscience and Consciousness, 11 July 2018

Maybe we should think of it like this: Transwomen are to women as adoptive parents are to parents. There are disanalogies of course, and the morality of adoption is a large issue in itself which I can’t do full justice to here. Still, the analogies are, I think, important and instructive.

An adoptive parent is someone who desperately wants to be a parent but can’t be one in the normal biological sense. (At any rate usually–there are families with a mix of biological and adopted children. But here I’ll focus on the commoner and simpler case.) So society has found a way for her to live the role of a parent, and to be recognised socially and legally as a parent, which kind of gets round the biological obstacle.

‘Kind of’: plenty of adoptive parents report an abiding regret that they aren’t biological parents, and there can be problems on either side of the adoptive relationship. It is clear that the existence of adoptive relationships creates psychological difficulties, both for the parents and for the children, that would not otherwise exist. But these problems are not big enough to make adoption a net bad thing.

One reason why not is that adoptive parents are, in the nature of the case, deeply committed to parenting. Unlike some biological parents, they aren’t parents by accident. And by and large–though unfortunately adoptive parents do suffer *some* sorts of discrimination–society recognises and values their commitment, and accepts them for many purposes as parents like any others, though of course there are contexts (blood transfusion, organ donation, testing for inherited illness) where the fact that they’re adoptive parents makes a difference.

Nobody sensible thinks that it’s all right, when you find out that someone is an adoptive parent, to get in her face and shout ‘Biology! Science! You’re running away from the facts! You’re delusional! You’re not a real parent!’ That would be incredibly rude and insensitive. It would upset her family. It would be importantly false: there is a perfectly good sense in which an adoptive parent most certainly is a real parent. Yet since this aggressive accusation is also, alas, only too intelligible to the parent who is subjected to it, it would also be stamping up and down in the crassest and cruellest way on what anyone can see at once is very very likely to be a sore point for her. (Here I speak, I’m sorry to say, from personal experience of analogous shoutings.)

Nobody sensible thinks that it’s an infraction of Jordan Peterson’s human rights to impose on him a social, ethical, and sometimes even legal requirement that he call adoptive parents parents.

Nobody sensible thinks that, if you refer to an adoptive parent as a non-parent, then you don’t owe it to that parent, as a matter of basic courtesy, to retract, correct, and apologise.

Read the full article in Conscience and Consciousness.

Hollywood and hyper-surveillance:

the incredible story of Gorgon Stare

Sharon Weinberger, Nature, 11 June 2019

In the 1998 Hollywood thriller Enemy of the State, an innocent man (played by Will Smith) is pursued by a rogue spy agency that uses the advanced satellite ‘Big Daddy’ to monitor his every move. The film — released 15 years before Edward Snowden blew the whistle on a global surveillance complex — has achieved a cult following.

It was, however, much more than just prescient: it was also an inspiration, even a blueprint, for one of the most powerful surveillance technologies ever created. So contends technology writer and researcher Arthur Holland Michel in his compelling book Eyes in the Sky. He notes that a researcher (unnamed) at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California who saw the movie at its debut decided to ‘explore — theoretically, at first — how emerging digital-imaging technology could be affixed to a satellite’ to craft something like Big Daddy, despite the ‘nightmare scenario’ it unleashes in the film. Holland Michel repeatedly notes this contradiction between military scientists’ good intentions and a technology based on a dystopian Hollywood plot.

He traces the development of that technology, called wide-area motion imagery (WAMI, pronounced ‘whammy’), by the US military from 2001. A camera on steroids, WAMI can capture images of large areas, in some cases an entire city. The technology got its big break after 2003, in the chaotic period following the US-led invasion of Iraq, where home-made bombs — improvised explosive devices (IEDs) — became the leading killer of US and coalition troops. Defence officials began to call for a Manhattan Project to spot and tackle the devices.

In 2006, the cinematically inspired research was picked up by DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which is tasked with US military innovation. DARPA funded the building of an aircraft-mounted camera with a capacity of almost two billion pixels. The Air Force had dubbed the project Gorgon Stare, after the monsters of penetrating gaze from classical Greek mythology, whose horrifying appearance turned observers to stone. (DARPA called its programme Argus, after another mythical creature: a giant with 100 eyes.)

Read the full article in Nature.

The sounds of parallel cinema

Salil Tripathi, Live Mint, 6 May 2019

Indian cinema reached modernity in the train scene in Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955), when two children, Apu and Durga, lost in a field, hear distant rumbling and see, for the first time, a train race through the landscape. It bridged the distance between a village and the big city, between where India cinema was and where it could go.

The New Wave too began with a train sequence. In 1969, Mrinal Sen’s first Hindi film, Bhuvan Shome, began with the camera pointed towards the railtracks as the train moves fast. Keeping pace with the engine’s rhythm is a glorious taan (flurry of notes), accompanied by the tabla, dholak, bongo and other Western percussion instruments, keeping to the train’s beat, as a female voice, singing the basic seven notes at a slower pitch, yet maintaining the tempo, presages what is to follow: railway officer Utpal Dutt’s obduracy meeting the simple village girl Suhasini Mulay’s innocence.

In commercial cinema at that time, songs became what film-maker Sangeeta Datta calls a ‘decorative extension of the star persona’. Background score was often used to heighten emotion. The title music was usually loud, reaching a crescendo when the film’s title—in English, Hindi and Urdu—would appear, and later, loud drums and instrumental music would emphasize plot twists and turns. Documentary-maker and author Nasreen Munni Kabir says: ‘In the 1970s’ commercial films, even if you did not understand the Hindi or the dialogue, the music itself indicated a comic or tragic situation that was being played out. Loud crying accompanied by the shehnai is one example.’

Shyam Benegal, whose Ankur (1974) was one of the harbingers of the New Wave, says: ‘Although sound came to the cinema more than three decades after its invention, its role was initially seen in the illustrative musical scores that accompanied the visual action—the sound of footsteps, doors opening or closing, and so on. Sound was meant to complement and be equal to the visual in its narrative ability. (Alfred) Hitchcock understood it well, and today most directors take that for granted.’ He finds the best examples from India in Ray’s work, and, among all Indian composers, Vanraj Bhatia (who composed music for most of Benegal’s more than two dozen films) understands it best, he says.

Bhatia’s contribution to the sounds of the New Wave is critical. Kabir says: ‘Bhatia brought a different musical mood to the films. His scores were restrained and atmospheric—far more held back than the obviously emotive and melodramatic background scores of popular films.’

Read the full article in Live Mint.

The images are, from top down: A graphic of DNA (source unknown); The Iraq Museum (from The Baghdad Post, photographer unknown); the SS Empire Windrush (photographer unknown); Dana Scutz’s ‘Open Casket’: A photograph of Sipho Mavimbela killed in Alexandra on June 18th, 1976 ( Photo: James Oatway/New Frame)