This essay, on John Milton, Phillip Pullman and the ambiguities of stories, was my Observer column this week. (The column included also a short piece on strikes in France.) It was published on 29 December 2019, under the headline ‘From Milton to Pullman, the quest for truth is riddled with ambiguity’.

‘A poem is not a lecture; a story is not an argument. The way poems and stories work on our minds is not by logic, but by their capacity to enchant, to excite, to move, to inspire.’ So writes Philip Pullman in his introduction to John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

Milton’s epic remains one of the greatest retellings of the Christian story, a work that has mesmerised writers through the generations from William Blake to Pullman himself. Pullman’s His Dark Materials, the striking BBC adaptation of which ended its first series last week, reworks Paradise Lost, turning its moral message on its head. Milton’s poem tells the story of the Fall; of Satan’s banishment from heaven for leading a rebellion against God and of his revenge in corrupting Adam and Eve and hence all humans, by tempting them to eat of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil.

In His Dark Materials, knowledge is seen not as corrupting but as liberatory; it’s the desire to keep certain knowledge forbidden that corrupts. Deeper down, though, what links the two works is a common reverence for human dignity and a recognition of the complexity, both of humans and of storytelling.

Milton wrote Paradise Lost to ‘justify the ways of God to men’. The star of the work, however, is not God but Satan, fanatical and malevolent, yet heroic in a most tragic way. As Blake observed of Milton, he is “of the devil’s party without knowing it”.

Milton was of ‘the devil’s party’ because he was driven by a deep suspicion of unwarranted authority. He supported the parliamentarians against Charles I and advocated the king’s execution, for which he was imprisoned after the Restoration in 1660. Milton’s revolutionary instincts led him also to champion freedom of conscience and speech. ‘Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties’, he wrote in Areopagitica, one of the great polemics against censorship.

However malignant Satan may be in Milton’s eyes, he cannot but reveal a certain sympathy for the leader of the rebel alliance. Nor can he ignore that Christian morality sits uneasily with his celebration of knowledge and free expression. It’s a conflict that plays out particularly in the figure of Eve, perhaps the most fascinating of Milton’s characters. Milton presents Eve as inferior and one whose place was to be submissive to authority, whether of Adam or of God. But Eve is also questioning of her status. “For inferior who is free?” she asks.

In Areopagitica, Milton insists on the necessity of confronting, not censoring, obnoxious views: ‘As therefore the state of man now is, what wisdom can there be to choose, what continence to forbear without the knowledge of evil?’ To be good, one has to have knowledge of, and be able to resist, evil. That same argument is put by Eve in Paradise Lost. ‘And what is faith, love, virtue unassayed?’ she asks Adam. A story may not be an argument, but an argument can become unpicked in a story, even one’s own argument in one’s own story.

His Dark Materials, too, is both driven by an argument, a vision of the world that challenges religious faith, and is deeply ambiguous about it. In Lyra Belacqua, the 11-year-old girl who is the central character of the trilogy, and the Eve of Pullman’s universe, we find someone whose very being answers the question: ‘For inferior who is free?’

For Pullman, knowledge is freedom. As explorer John Parry tells his son Will (the avatar of Adam): ‘Every little increase in human freedom has been fought over ferociously between those who want us to know more and be wiser and stronger, and those who want us to obey and be humble and submit.’

Yet, Pullman suggests, neither the search for knowledge, nor the relationship between good and evil, is straightforward. Lyra’s father, Asriel, is both the man who begins the struggle to obtain the forbidden knowledge and the man whose obsession with knowledge can make him seem ‘mad, wicked, deranged’ and leads him to sacrifice Lyra’s best friend to further his quest.

Humans are complex and contradictory creatures. And so necessarily are the stories we tell to make sense of ourselves and our world. Every story is open to many readings.

Reasoned argument and clarity are an indispensable part of our quest for knowledge. So are stories and their ambiguities. They are a celebration of the human capacity to find meaning and a recognition that meaning is not something to be discovered but something that humans create. From Adam and Eve to Lyra and Will, it is that search for meaning that enchants, excites, moves and inspires.

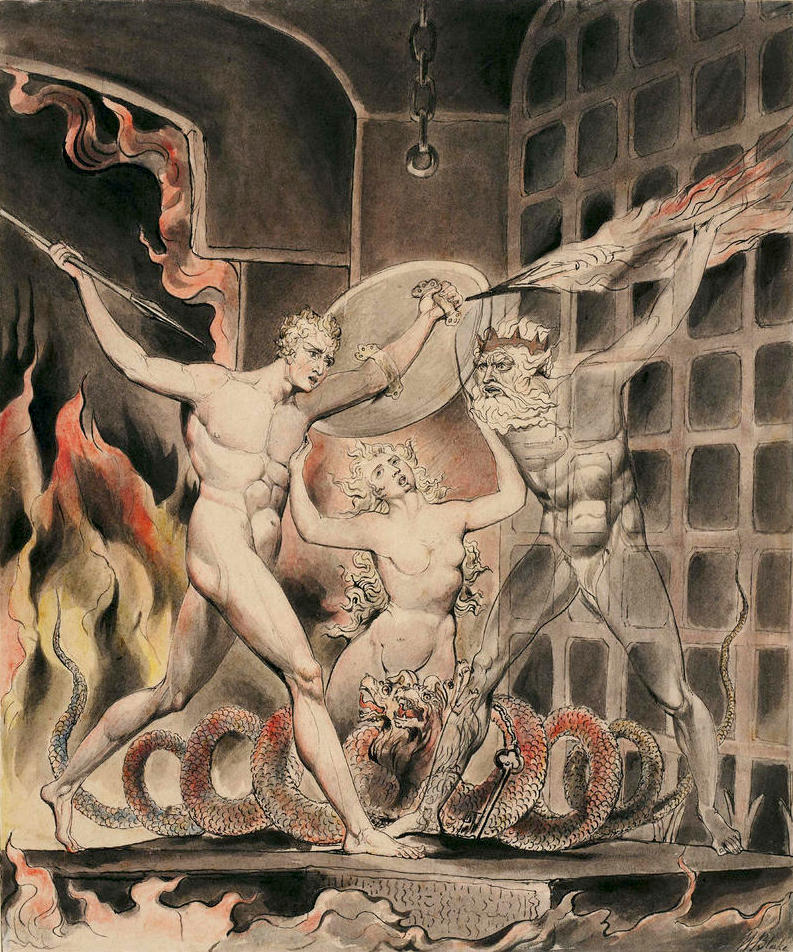

The image is one of William Blake’s illustrations of Paradise Lost, ‘Satan, Sin, and Death:

Satan Comes to the Gates of Hell’.