I mentioned in my last post the attempts by the UN, UNESCO and WIPO to give certain groups, particularly indigenous groups, control over traditional culture, and of the dangers inherent in such an approach. I am publishing here the transcript of a BBC Radio 4 Analysis programme that I wrote and presented in 2004 which explored the issue of ‘Who owns culture?’. You can listen to an audio of the programme, too.

‘Who owns culture?’, Analysis, BBC Radio 4,

29 July 2004

Taking part in the programme, in order of appearance, were Jack Lohman, Director of the Museum of London; Lola Young, cultural consultant; Michael Brown, Professor of Anthropology, Williams College, Massachusetts, and author of Who Owns Native Culture?; Robert Foley, Professor of Human Evolution, University of Cambridge; Neil MacGregor, Director of the British Museum; Norman Palmer, Professor of Law, Art and Cultural Property, London University; and Adam Kuper, Professor of Anthropology, Brunel University.

KENAN MALIK Museums used to be dusty repositories of arcane artefacts. Today they are fast becoming sites of conflict and controversy.

JACK LOHMAN I think it’s high time for museums to behave morally towards their collections and towards the communities that they serve.

LOLA YOUNG The problem with some of those collections is not just about the way in which they’re collected; it’s about the motivation behind them. So if something is collected in order to, for example, demonstrate the superiority of Europeans, the inferiority of Africans or Indians so called other peoples, then that is obviously highly problematic.

MICHAEL BROWN The problem is that if you try and do an exhibit that doesn’t offend somebody, you end up with an exhibit that’s so uninteresting and insipid that it’s really of no use at all.

KENAN MALIK Jack Lohman, director of the Museum of London, cultural consultant Dame Lola Young and Michael Brown, professor of anthropology at Williams College, Massachusetts. What does it mean for museums to act morally? Should they become more socially relevant by promoting the cultural aspirations of the communities they serve and whose artefacts they display? Is it right for museums to hold on to objects that belong to other cultures? The great museums of the West are largely the products of Empire. In our more enlightened times, curators seem increasingly unsure what to make of their own collections. Robert Foley, Professor of Human Evolution at Cambridge University and former director of the University’s Duckworth Museum.

ROBERT FOLEY I think there’s certainly a crisis of confidence in many museum people and the communities that work there, that museums have a particular image in relation to the places from which much of their material has come and they feel that in a way building relationships with emerging nations and communities is an important way of trying to restore the notion of museums. I personally think that museums, on the other hand, should not be ashamed of their past. I think if we look at what we find in the British Museum or we find in the great museums of Europe, we have saved there a history of the world which might otherwise have easily have been lost and which now acts to inform people in ways that can only be for the good.

KENAN MALIK But did the British Museum save the world or just plunder it? For many people, the critical question in judging a museum is how it acquired its collections. Among the British Museum’s most prized possessions are the Elgin Marbles and the Benin Bronzes. In the early nineteenth century, the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Lord Elgin, removed from the Parthenon in Athens of some of its best statues and friezes and sold them to the British Museum. Nearly a century later a punitive British expedition to Benin (in modern day Nigeria) looted some of the nation’s best art treasures. Today there are vocal campaigns for the Marbles and the Bronzes to be returned to Greece and to Nigeria. Neil MacGregor, director of the British Museum, thinks, however, that both are better displayed in London.

NEIL MACGREGOR In the British Museum you can see how that Greek art emerges from a whole tradition of the Eastern Mediterranean and how it invigorates a different tradition in Rome, India and the rest of Europe. In the British Museum, they are clearly one of the great achievements of the whole of mankind.

KENAN MALIK Would you say the same for the display of the Benin bronzes, for instance?

NEIL MACGREGOR I would say very much the same of the Benin bronzes. One of the extraordinary things about the Benin bronzes is that when they arrived in London, they completely transformed the way people in Europe thought about Africa. It was the presence of the Benin bronzes and the extraordinary sophistication of making that made it completely impossible for Europeans to go on thinking of Africa as not having its own culture and a very great culture. The circumstances of the taking of the Benin bronzes were violent, as we all know, and there’s a great deal to be said and debated about what happened there. But if we look at what happened when they arrived, it seems to me that from then on it was totally beneficial. It changed the way Europeans thought of Africa and it enriched a worldwide cultural tradition.

KENAN MALIK But isn’t it unethical for museums to cling on to items that were originally looted or stolen? Not necessarily, Neil MacGregor argues. The importance of the British Museum to the world today, he suggests, outweighs the dubious provenance of some of its artefacts.

NEIL MACGREGOR I think the purpose of the British Museum is to allow people to see that all the societies of the world and all the cultures of the world are interconnected. That’s the one big thing that the British Museum, better than any other museum in the world probably, can allow you to do – to see the oneness of humanity.

KENAN MALIK Viewing the interconnectedness of cultures and peoples, is that what you mean when you describe the British Museum as a ‘world museum’?

NEIL MACGREGOR I think the British Museum is in a sense the memory of mankind, as Ben Okri said. And the extraordinary thing about it is that it was set up in 1753 to gather together things from all over the world, but always to be held open free to people from anywhere in the world. So from the beginning, this very idealistic notion, if you like, of trustees holding for the entire world the means of understanding the entire world.

KENAN MALIK A cynic might suggest that ‘world museum’ is just a fancy phrase to allow the British Museum to cling on to its treasures. After all, the museum may be free to anyone in the world but most people in the world can’t take advantage of its largesse. Yet it’s not just rich tourists or white middle class Britons who benefit from the Museum’s treasures. Around 30 per cent of Londoners are non-white and the fastest growing population is African. In an age in which museums are seeking to be socially inclusive, some curators believe that cultural objects from around the world should be used to attract groups – such as African-Caribbeans or Asians – who might otherwise walk right past their doors. Lola Young was until recently head of cultural policy for the Great London Authority. Does she agree with this approach?

LOLA YOUNG It’s important for diaspora peoples from wherever can see those objects in their newly adopted or more recently adopted homelands. I don’t have a problem with that. Where I have a problem is where that is wheeled out as a reason or an excuse when the objects and artifacts themselves aren’t treated with appropriate respect. If we look, for example, at the so-called Hottentot Venus, Sara Bartman, who came to Europe in about 1810. When she died in Paris, in 1815, her body was subsequently put on display in the Musee de l’Homme and was on display until the middle of the 20th century – until the late 20th century actually – despite many requests for her remains to be returned. They were finally returned to South Africa to the Koikoi tribe in 2002 and this was after some negotiation between Jacques Chirac and Nelson Mandela. There is a symbolic value attached to the Hottentot Venus because she was held up to be something that was completely anonymous, sub-human, and that attitude towards Africans from Europeans became literally embodied in her body both alive and dead.

KENAN MALIK An exhibit such as the Hottentot Venus may be a thing of the past. But Western museums still hold tens of thousands of human remains – skulls, skeletons, bones. And even more than artefacts, such remains generate anger and controversy, and demands from source communities for their return and reburial – as the Museum of London’s Jack Lohman experienced first hand when he was living in South Africa.

JACK LOHMAN I think I went through one of the most traumatic periods of my life living in South Africa. I was looking after the National museum in South Afruca which is oldest in Africa. It has 788 human remains in boxes. And I remember one day I had a delegation of 70 people storm into my office and say to me: ‘We are not leaving your office until you release the human remains in the museum’. I’m not sure whether museums should be mass graves. For me there’s an issue whether museums are the right place to be holding on to this material. We began a process of returning these various trophies if you like back to their communities. It was a very dramatic moment. It really influences and makes me think very hard about what we keep in museums. I think culture is a sort of human right. And therefore giving those cultures to whom those objects or artefacts belong to. I think it’s part of restoring human rights.

KENAN MALIK The debate about human remains has been especially fierce in America, Australia and New Zealand, where guilt about the treatment of indigenous peoples – Native Americans, Aborigines and Maoris – runs deep. Museums in these countries have thrown open their storage rooms, and returned thousands of bones to source communities for burial. In Britain the government-appointed Working Group on Human Remains recently published its report on what to do with the remains held by English museums. Its chairman is barrister Norman Palmer, Professor of Law, Art and Cultural Property at London University.

NORMAN PALMER We, to a large extent, base our recommendations on the need to treat indigenous people in the same way or a truly analogous way to that in which other people are treated. Let me give you some examples. Under English law certain people have the overriding right to the delivery up of members of their family for burial. Those are the personal representatives. It might be the executors if there is a will or administrators. If there isn’t, this is an absolute right by law and no counter argument, for example of the scientific value of research, can be allowed by law to defeat that right. In the report what we are saying is what argument is there for treating indigenous peoples differently when their remains are in museums rather than in hospitals. If we’re going to adopt notions of family, kinship and ancestry, we should be careful not to confine these in any insular or arbitrary or discriminatory way to Western notions or paradigms of kinship and ancestry and family. So that if people have within their own community – and this would be the community from which the remains emanated in the first place – a relationship or responsibility towards the remains, which was akin to that under their own culture of close family or direct genealogical descendents, then we would say they too should have the right to say what should happen to their family. We are not so insular as to believe that our way is the only way.

KENAN MALIK Most people would understand if museums had to release human remains to close relatives. But does it make sense to insist that bones thousands of years old are off-limits for study or display because a particular culture views even remote ancestors as close kin? In any case who exactly are indigenous groups? And how do we know what they want? Michael Brown, Professor of Anthropology at Williams College, Massachusetts, and author of Who Owns Native Culture?.

MICHAEL BROWN Where indigenous peoples have formally recognised political organisations that are recognised by the state and are authorised to make and develop policies, then that’s the group that one deals with. Now internal to the community, of course, there may be great debates about whether elected political leaders or even traditional authorities of one sort or another have the power and the authority to make those decisions. Who do you talk to? How do you get the consent that you feel you need before you can move forward? Even the question of who is indigenous gets extremely vexed as indigenous peoples inter-marry with non-native communities. I mean right now American Indians have the highest rate of out marriage of any ethnic group in the United States. And that’s a problem that people are wrestling with in North America, they’re starting to wrestle with in Australia. And that’s going to be the next battleground – trying to determine who qualifies as indigenous in the first place.

KENAN MALIK Indeed, some anthropologists argue, indigenous people are not just difficult to define, they are a Western invention. Adam Kuper, Professor of Anthropology at Brunel University.

ADAM KUPER These are the people who in the 19th century were described by anthropologists as so-called primitive people – hunters and gatherers living in far flung parts of the world. They were seen as being somehow at the bottom of the evolutionary chain. Today, a hundred and fifty years later, after anthropologists completely deconstructed these notions of hunter gatherers, of primitives, of racial exclusivity, all these Victorian notions are being reconstituted with the support of NGOs, World Bank, United Nations in order to construct a new category – the indigenous peoples of the world – who are identical, it turns out, to these primitive peoples. And they are thought to have some sort of stable culture which dates back before colonialism, which must be somehow reconstructed, handed back to these people. It’s phoney ethnography. It seems to me mumbo jumbo anthropology.

KENAN MALIK Mumbo jumbo anthropology it may be but it has captured the imagination of many in the West. So much so that even when there are no claimants to bones or artifacts, museums insist on burying them. You might think that a government would only bother to set up a Working Group on Human Remains, and consider changing the law, if there’s a real issue to address. Think again. There have only ever been 31 claims for the return of human remains held in British museums. But some curators want to do the moral thing anyway. Jack Lohman of the Museum of London.

JACK LOHMAN Thanks to a very generous grant from the Wellcome Trust we are researching the plague pits. The greater part of the sample is male. The majority have come from local monasteries. Generations of monks etc. So obviously monks do play around but the majority won’t have had ancestors as such, and therefore to try and track down ancestors would be a very difficult task and probably a very expensive task, and would involve DNA testing the whole of London probably. We’ve got huge amounts of material. But there’s not enough information about them. I’ve got 9 curators of human remains in the museum. It’s more curators than possibly any other national museum in Europe working on human remains or possibly any other University department studying human remains at the moment, and that is because we’ve got such a large volume of them that we need to go through them. When we’ve finished, we plan to put them in a, ideally in a catacomb where they can be sealed up. Once we’ve done them then the time will be to place them somewhere beyond the museum.

KENAN MALIK Is that not just for your benefit and nobody else’s. After all nobody is claiming those bones. So is it not a way of assuaging your moral guilt about those bones?

JACK LOHMAN If you have collections of male monks who gave their life to the church and you have 10 thousand of them let’s say, I think there is a moral obligation to place them in sacred ground not keep them in the museum.

KENAN MALIK But museums have a responsibility not so much to the dead as to the living. And part of that responsibility is to use the dead to elicit knowledge that might benefit us. Here’s Robert Foley of Cambridge University.

ROBERT FOLEY They’re an absolutely fundamental source of information about human history, especially global human history. And of course because they’re the bodies of people that lived, they tell us about their life, their death, their diseases, whether they were healthy, whether they died in combat or from some other illness and so on. So it’s a rich history from which we have really learnt so much about humans not just as European history but as the whole global phenomenon. There are examples where human remains have been used for medical advances – various research done into sort of orthopaedic surgery, obviously a lot of work done in forensics in the ability to identify people and so on. So there is a utility to it, but I think it’s wrong to say that that is the primary driving force. It is in no doubt that this sort of work is basically curiosity driven in the sense we’re looking for knowledge for its own sake. One example is the way in which we now think of humans as having evolved in Africa. Fifty years ago we weren’t thinking about an African origin. Fifty years ago, we were thinking in terms say of racial categories. We don’t think in that way now. So new questions come up and we need to re-examine material with those new ideas in mind.

KENAN MALIK There are, though, tens of thousands of bones in museums. Do scientists really need them all? Michael Brown of Williams College.

MICHAEL BROWN There have been studies done of the percentage of Native American remains, held by US museums that haven’t been studied by anybody and it’s a shockingly low percentage. Well under a quarter of them have never been catalogued in the most elementary way, and we’re talking about as many as hundred thousand individuals represented in these collections at the national level. So the question that Indians ask is ‘Well, If these bones are so darn important to you, why is it that you haven’t done anything with them for the past hundred years?’

KENAN MALIK What worries scientists, though, is that bones that might be vital to research may be lost forever. Robert Foley.

ROBERT FOLEY If the Palmer Report in all its recommendations was implemented, I think it would have a major impact on our research. The onus would be on us as the holders of collections to as it were go out and find either biological descendents or cultural descendents or related groups or national or local institutions which might want that material back. That would be a vast undertaking which I think would absolutely devastate the resources that most collections have available to them. The return of material would mean that the collections would lose a very significant part of human diversity.

NORMAN PALMER The report says nothing of the kind. The report says that in certain circumstances museums should have an obligation to identify those people who are sufficiently closely related to the remains to be entitled to request them back. It makes it perfectly plains in the notes to recommendation 15 that ‘identify’ means respond to a claim and try to verify whether that claim is justified or not.

KENAN MALIK Norman Palmer. Whoever is right in this – and even members of the Working Group disagree on the implications of the report – the final decision rests with the government. It’s just published a consultation paper asking for responses to the Palmer report – but there is no indication of its own views on the matter.

And it’s not just bones that scientists fear losing. Artifacts too are being lost as museums accede to the demands of indigenous groups. Harvard University’s Peabody Museum deliberately allowed a historic set of photographs to disintegrate because the Navajo tribe objected to non-tribal members viewing the rituals they depicted. There are other ways, too, in which objects are being lost, as anthropologist Michael Brown points out.

MICHAEL BROWN Certainly when objects are returned to Indian tribes through the repatriation process, the tribes are free to do what they like with these objects and in some cases tribes have made it absolutely clear that their intention is to reintegrate them into ongoing rituals until such time as the objects are essentially worn out and discarded. And so in that sense, I guess, there is a destruction of objects and of information associated with it.

KENAN MALIK ‘So what?’, you might say. It’s their culture, their artifacts, they can destroy them if they want to. For too long, argues Lola Young, Western nations have been exploiting non-Western peoples. We’ve got to get used to the idea that we can’t do what we like with other people’s cultures, whether these consist of bones, artifacts or even symbols.

LOLA YOUNG If we look at the Olympic Games in Australia in Sydney. It was very clear that the Australian authorities wanted to promote Australia as a country that had come to terms with its past and opened its arms, as it were, to diversity. Now the extent to which some of the Aboriginal people feel that that is actually the case and how that actually pans out on a day-to-day basis for them is another question altogether. So I think that that’s absolutely legitimate that a group of people should then say well we want to have some sort of control over how we’re portrayed and how our symbols and our symbolism are used.

KENAN MALIK In one current court case in Australia, Aborigines are demanding that the national airline Quantas stop using the kangaroo logo as it’s an Aboriginal symbol. In another case, they are seeking copyright over all photographs and paintings of the Australian landscape which they say is central to their spiritual life. Where will this end? Must the British government approve every production of King Lear and Othello? Should only Jamaicans be able to play reggae? Professor Adam Kuper of Brunel University.

ADAM KUPER I think the notion of ownership is certainly meaningful and one could own objects which you might describe as cultural objects because you had made them or you had designed them or you had bought them, but to claim some sort of ownership on the grounds of descent from a group of people who might in the distant past once have invented those objects seems to me to be bizarre, seems to me absolutely impossible. Are we going to, as English people, ask others to pay a copyright fee when they play cricket? It’s ridiculous.

KENAN MALIK Ridiculous it may be, but cultural bureaucrats seem hooked on the idea. UNESCO has suggested that ‘each indigenous people must retain permanent control over all elements of its own heritage’, including ‘songs, stories, scientific knowledge and artworks.’ It has even suggested the setting up of ‘folklore protection boards’. UNESCO’s push to protect every culture, Michael Brown argues, is counterproductive.

MICHAEL BROWN Every culture or every nation is supposed to have members of its culture provide inventories of all elements that are subject to protection, but of course that is protecting by making something public. That runs foul of the sense of many Aboriginal Australian and Native American groups that certain kinds of information simply should not be made public, should only be held and used by whatever sub-group of the population – typically religious leaders – is empowered to use it safely and effectively. At the local level indigenous peoples themselves are moving towards greater and greater secrecy.

KENAN MALIK Isn’t there also a case of a native American group trying to dissuade outsiders from learning its language so as to be able to better protect its culture?

MICHAEL BROWN Well I was told that people, contract workers who work in Zuni, New Mexico, are specifically prohibited from learning the language of the Zuni people, the assumption being – as you mentioned earlier – that learning the language gives them access to ritual secrets and others forms of understanding that they simply should not have access to.

KENAN MALIK In a different context though, would we not call this xenophobia or racism?

MICHAEL BROWN Well it’s true – if the shoe were on the other foot, if Anglo Americans were forbidding native Americans from speaking English, it would be considered a completely unacceptable racist policy.

KENAN MALIK The campaign for the repatriation of artifacts and remains, and for the protection of minority cultures, is motivated by the best of intentions. Its consequences, though, can be deeply troubling. It presents an idea of culture as fixed and immutable, and as something that people own by virtue of their biological ancestry – an almost racial view of the world. Many museums now accede to demands from indigenous groups that in any other context would be seen as unacceptable. Some, for instance, ban women or non-tribal people from viewing certain parts of their collections. Others prefer to hide objects away in basementS rather than risk causing offence. This confusion and insecurity on the part of museums needs to be sorted out, says Norman Palmer – particularly where human remains are concerned.

NORMAN PALMER The existence of all these questions argues incontrovertibly for an independent resolution process. These questions must be examined. We do not say that one side is incontrovertibly right or wrong. What we say to each side is if you’ve got a good, arguable case, submit that case to independent evaluation.

KENAN MALIK Do you think there should be binding guidelines on museums as to how they should approach the question of human remains that they possess in their collections?

NORMAN PALMER Our position is that the position of human remains – again similarly to those in hospitals – the position of human remains in museums is sufficiently important that it should be subject to regulation by a code of practice. This code of practice would be enforced, if you like, through a licensing system and museums granted the licence would depend upon its adherence to the code of practice.

KENAN MALIK Museums are not keen on enforced guidelines, preferring a case-by-case approach to every dispute. But, says the British Museum’s Neil MacGregor, there is one area where binding international agreements are not only welcome but may defuse many of the currents disputes about cultural repatriation.

NEIL MACGREGOR We have in the last thirty, forty years, with the growth of international exhibitions, seen an unparalleled sharing of world culture. There has never been such universal access to the culture of the whole world as there has in the last thirty years because of the phenomenon of exhibitions. That has of course been focused overwhelmingly on the rich countries of the world. I think the challenge is to allow as many of our objects as possible to be seen in different contexts – in the contexts of our own museums and in other contexts round the world – including, of course, and especially, the countries of origin. So what we need is a legal framework that will enable that to happen.

KENAN MALIK What you’re saying is that you’d like to build a series of universal museums across the world?

NEIL MACGREGOR Absolutely. I think what we need across the world are series of the experiences of universal museums through temporary exhibitions and revolving loans, but we need a legal framework that would allow that to happen.

KENAN MALIK The idea of a universal museum may not be fashionable these days. But Neil MacGregor’s vision seems to me highly commendable. We shouldn’t be ashamed of the treasures possessed by great institutions such as the British Museum. Nor of the Enlightenment ideal of a museum as an institution that can help create more universal forms of knowledge by collecting from across ages and cultures. Cultures are not private property. They belong to us all.

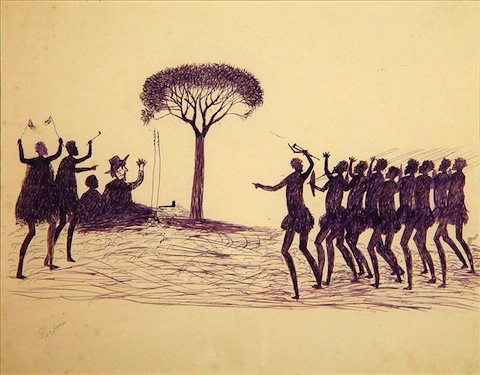

The images are, from top down, Tommy McCrae, ‘Buckley with a group of Aborigines’, c 1880s, Koorie Heritage Trust; a Benin Bronze; an eighteenth century sketch of visitors viewing Sarah Baartman, the so-called Hottentot Venus, in an ‘exhibition’; a skeleton of a 14th century woman buried in St Mary’s Graces, London, the Museum of London; skull of the so-called Kennewick Man, an ancient Native American skeleton, Burke Museum, University of Washington; William Barak, ‘Ceremony with serpent’ (c 1830), the National Gallery of Victoria; drawing of the Tlingit Raven, central to a number of Native American Creation stories; one of the Elgin Marbles at the British Museum.

Transcript © BBC