This is the opening to my essay on Hannah Arendt and her significance today, published in the Observer on 4 May 2025. You can read the full version in the Observer.

“What happened? Why did it happen? How could it have happened?” asked Hannah Arendt in a preface to The Origins of Totalitarianism. These were “questions with which my generation had been forced to live for the better part of its adult life”.

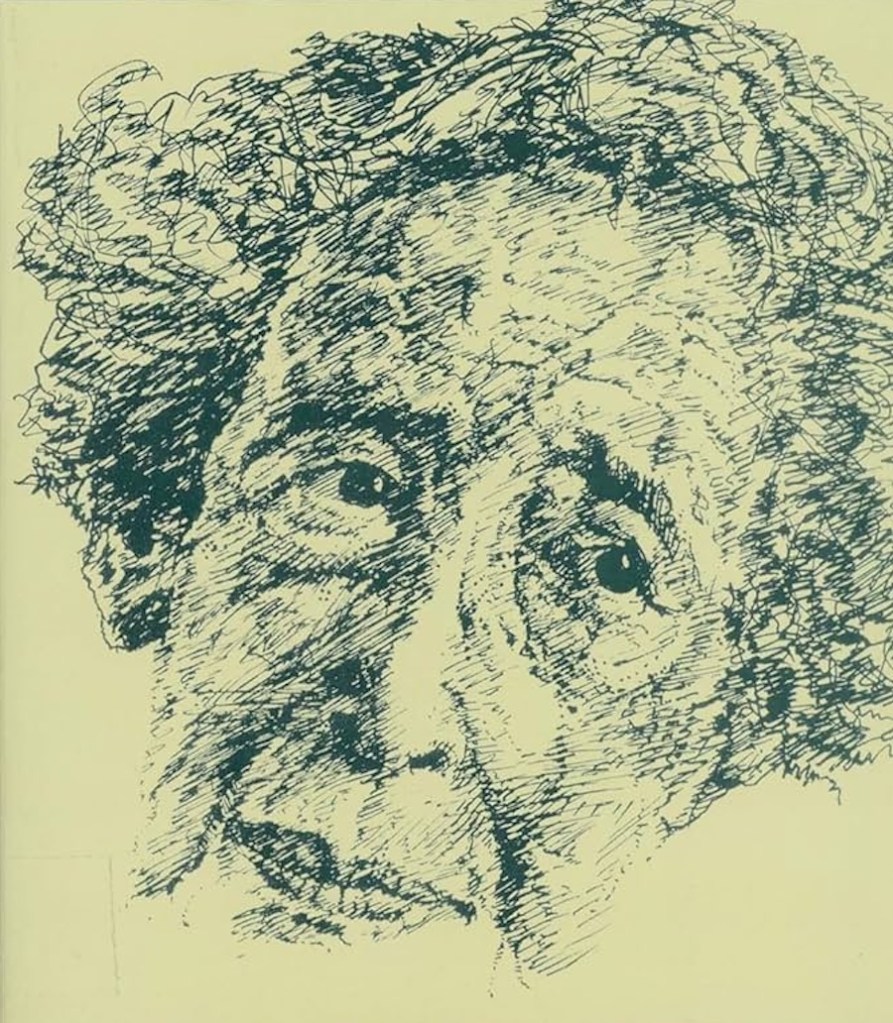

Among the most influential political thinkers of the 20th century, Arendt had, as a Jew, fled Nazi Germany in 1933, eventually finding refuge in America. Now a new edition of her famous 1951 work, including two additional chapters, has been published.

The Origins was not conceived as a book about totalitarianism. The first two parts dissect antisemitism and imperialism, respectively. Written in the mid-1940s, these two sections were to have been the core of the book, with a concluding chapter, “Race-Imperialism”, on the Holocaust.

Then came the Cold War. A third section on totalitarianism – “largely an afterthought”, the Arendt scholar Margaret Canovan observed – was written as the iron curtain descended and the Berlin airlift began. Arendt’s inventory of “elements” underlying totalitarianism – imperialism, racism, antisemitism, the decay of the nation state, the “alliance of capital and the mob” – made more sense in relation to Nazism than to Stalinism. But as the Cold War intensified, critics ignored much of this – especially Arendt’s autopsy of imperialism – in favour of a simplistic analogy between two totalitarian systems. Which is a pity, because the themes that preoccupied Arendt are central to our world, too. Her ideas should still command our attention.

The “scramble for Africa” at the end of the 19th century, Arendt argued, inaugurated a new imperialism that was “the preparatory stage for coming catastrophes”. Expansion became an end in itself. A new form of racism so dehumanised colonial subjects they were transformed into objects for extermination. A novel kind of bureaucracy substituted for democratic governance, and brute violence replaced the rule of law.

The large-scale slaughter of colonised peoples had long preceded the scramble for Africa. Arendt’s description of colonial racism was itself tainted by racism. “The overwhelming monstrosity of Africa – a whole continent populated and overpopulated by savages,” she wrote – “so frightened” Europeans that “civilised man … no longer cared to belong to the same human race” as the “savages”.

Yet for all her blind spots and prejudices, in showing how imperialism forged a template for totalitarian rule, Arendt was closer to anticolonial thinkers such as Aimé Césaire and Frantz Fanon than to most European intellectuals of the time.

Read the full version of the essay in the Observer