This is the opening to my essay on the legcy of Frantz Fanon, published in the Observer on 27 July 2025. You can read the full version in the Observer.

“Every brother on the rooftop can quote Fanon”, the Black Panthers’ Eldridge Cleaver once claimed. In the 1960s, Frantz Fanon, the Caribbean-born Algerian revolutionary, was a hero of Black Power and national liberation movements, drawn as they were to his excoriation of colonialism. By the 1980s, Fanon had become an icon of postcolonial theory, lauded as a critic of the Enlightenment and a progenitor of identity politics. Today, as Gaza is laid to waste, some have seized on Fanon to justify the Hamas slaughter of 7 October.

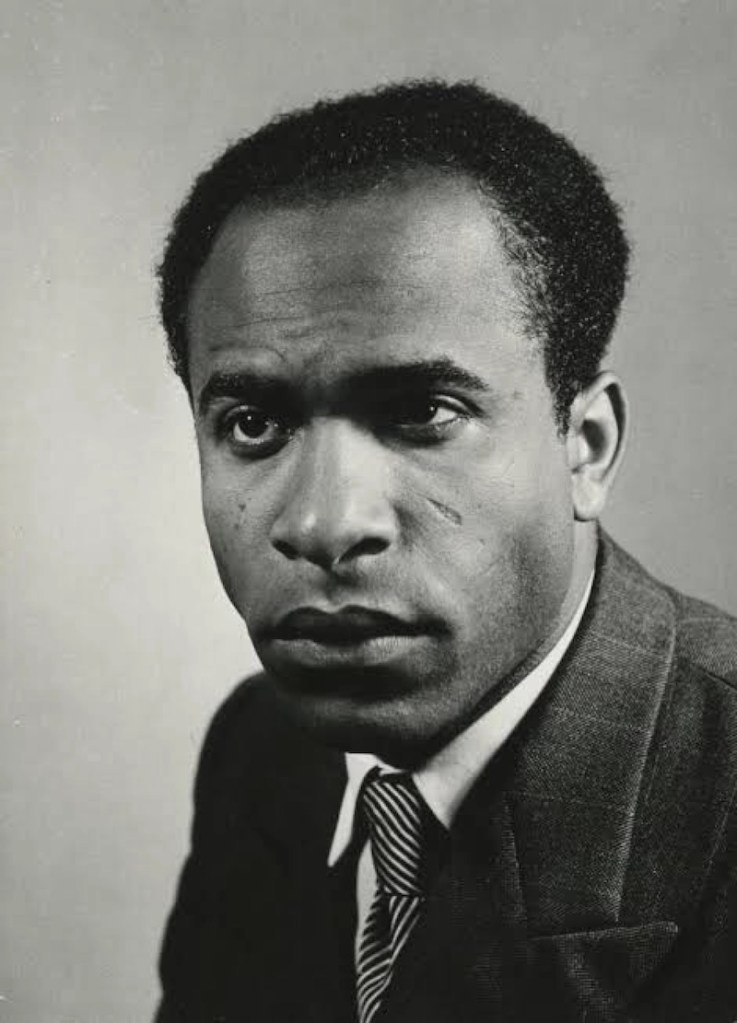

Ever since his untimely death from leukaemia in 1961, Fanon has been turned into a mythic figure, emblematic of various causes, admired and loathed in equal measure. Yet Fanon was a far more conflicted and allusive thinker than the myth suggests. This month marks the centenary of Fanon’s birth, an apposite moment at which to reassess his legacy.

Born in the French colony of Martinique, Fanon joined the Free French forces in 1943 as a teenager. Believing that “freedom is indivisible”, he wanted to enlist in the global fight against racism and fascism. What he discovered was a French army that itself was constructed as a racial hierarchy. As it crossed into Germany, Fanon’s regiment was “whitened” by the removal of all African soldiers. He had been “deluded”, he wrote angrily to his parents. Fanon, though, never abandoned his belief in the indivisibility of freedom; only, he now recognised that those who most proclaimed their fidelity to freedom often also viewed it as the privilege of a few.

What Fanon had discovered was a contradiction that has shaped the modern world – between societies that defined themselves through a commitment to equality, and social practices that denied such equality to the majority of people.

Read the full version of the essay in the Observer.