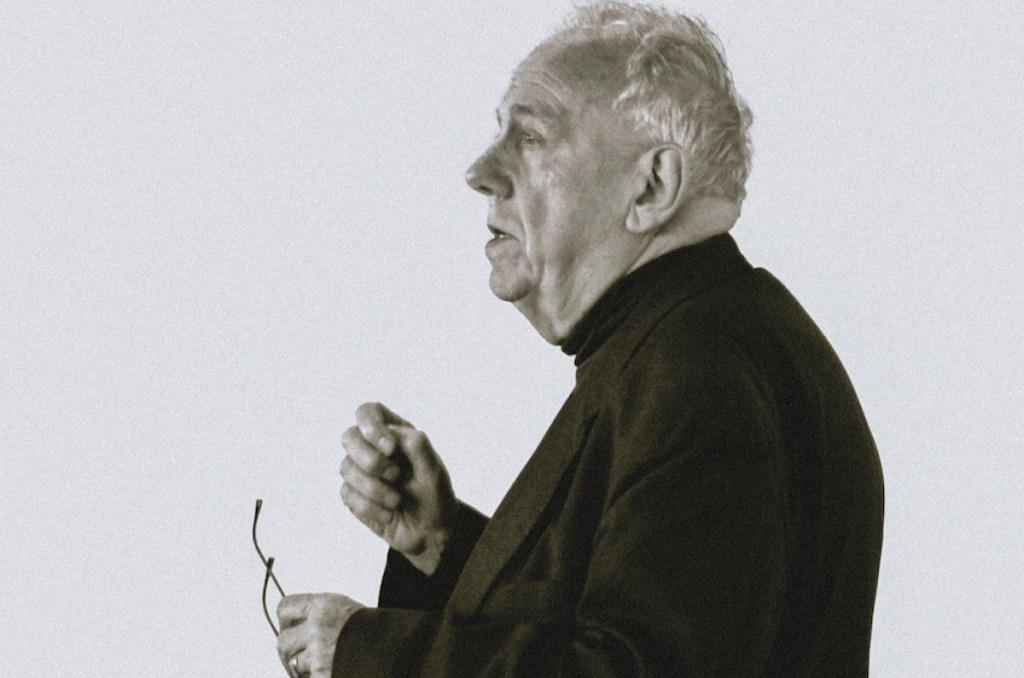

This is the opening to my essay on the the philosophy of Alasdair MacIntyre, rpublished in the Observer on 1 June 2025. You can read the full version in the Observer.

“Since I understood liberalism,” Alasdair MacIntyre once told an interviewer, “I have wanted nothing to do with it.” His death, last month, has robbed us of one of the most important moral philosophers of the past century. Born in Glasgow in 1929, he spent most of his life teaching in America. The issues with which he wrestled – the problems of liberalism, the degradation of moral thinking, the nature of belonging and identity, the significance of culture and tradition – now dominate much contemporary debate.

MacIntyre trod a long and convoluted philosophical path, starting as a Marxist, being drawn in the 1970s to Aristotelian virtue ethics, and eventually converting to Catholicism. Throughout this journey, he observed, “my critique of liberalism is one of the few things that has gone unchanged”.

For MacIntyre, liberalism not only fails adequately to understand an individual’s embeddedness in society but also fractures social bonds through its celebration of individualism and of the market. This argument was trenchantly expressed in his most famous book, After Virtue, published in 1981.

Moral life, MacIntyre argued, has been hollowed out. Everyone uses terms such as “ought” and “should” without really understanding them. The reason is that modernity, and the Enlightenment in particular, cut the moral link between the individual and society. In the premodern world, moral life was rooted in the concept of telos – the belief that human beings, like all objects in the cosmos, exist for a purpose. In human society, telos was defined by one’s role in the community. The purpose of a labourer was different from that of a king; that of a brother from that of a mother. To be good was to act in a way that fulfilled their purpose.

Modernity destroyed such community-defined notions of good and bad. Enlightenment thinkers came to see humans as agents possessing no purpose apart from that created by their own will and desires. Such individual autonomy, MacIntyre argued, created a moral vacuum, turning morality into a form of consumer choice.

Read the full version of the essay in the Observer.